Part II: Beijing’s extraordinary mission to unseat King Charles as Head of the Commonwealth

Last week Mark Toth and co-authors Jon Sweet and Alan Jenkins posted the first instalment of four looking at the future of the Commonwealth. In Part II they lay bare Beijing’s ambitions to buy up the Commonwealth, and so put the Queen’s legacy in peril.

Sunny blue skies, “flecked with white clouds” majestically bore witness to Queen Elizabeth II’s memorial procession from Holyroodhouse Palace to St. Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh. Flanked by King Charles III, Princess Anne, Prince Andrew, and Prince Edward walking on foot, the Queen’s Scottish crown atop her “flag-draped coffin” glistened in the sun as a golden beacon of her Commonwealth legacy. The Queen’s legacy, however, is in peril – as is her heir’s succession as the third head of the 56-member alliance.

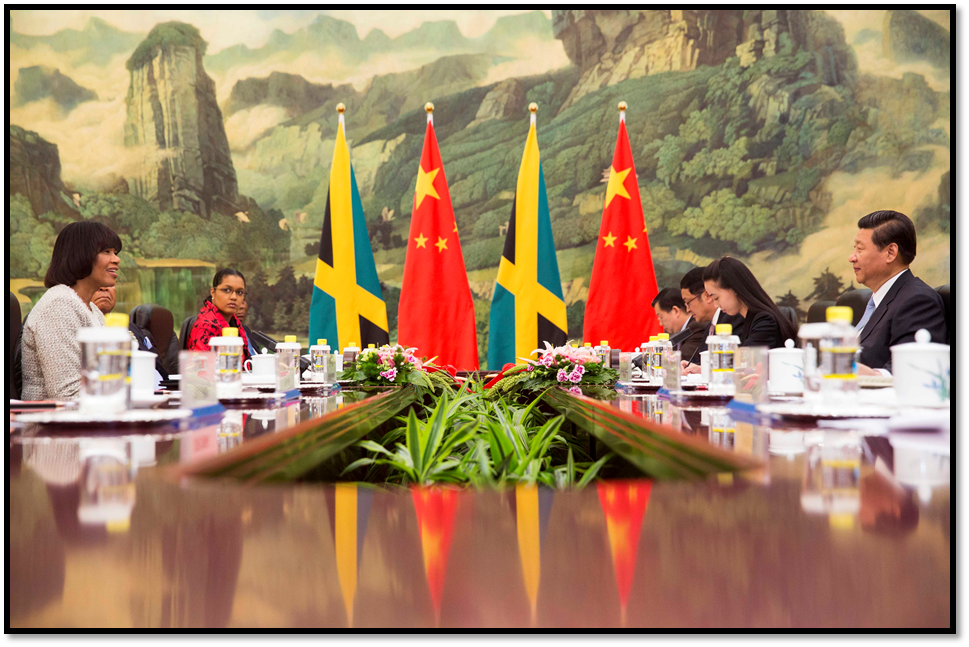

4,933 miles away in the gardens and interconnected lakes of the Zhongnanhai in the Forbidden City in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping – a modern-day Jacobite pretender – is intent upon commandeering Queen Elizabeth’s Commonwealth legacy and marginalising, if not, displacing King Charles in the process.

Xi, in effect, is waging a high-stakes hostile takeover attempt of the Commonwealth. Fanning the flames of republicanism – especially across the trade winds of the Caribbean – is only condition setting for Xi’s proxy fight. The means, however, is cold hard cash and heavy investment in infrastructure that all ties strategically into Beijing’s $1tn Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The consequences of Beijing’s “buying up” the Commonwealth are far reaching, including expanding the “international use” of the yuan, with the ultimate goal of supplanting the USD and GBP as reserve currencies.

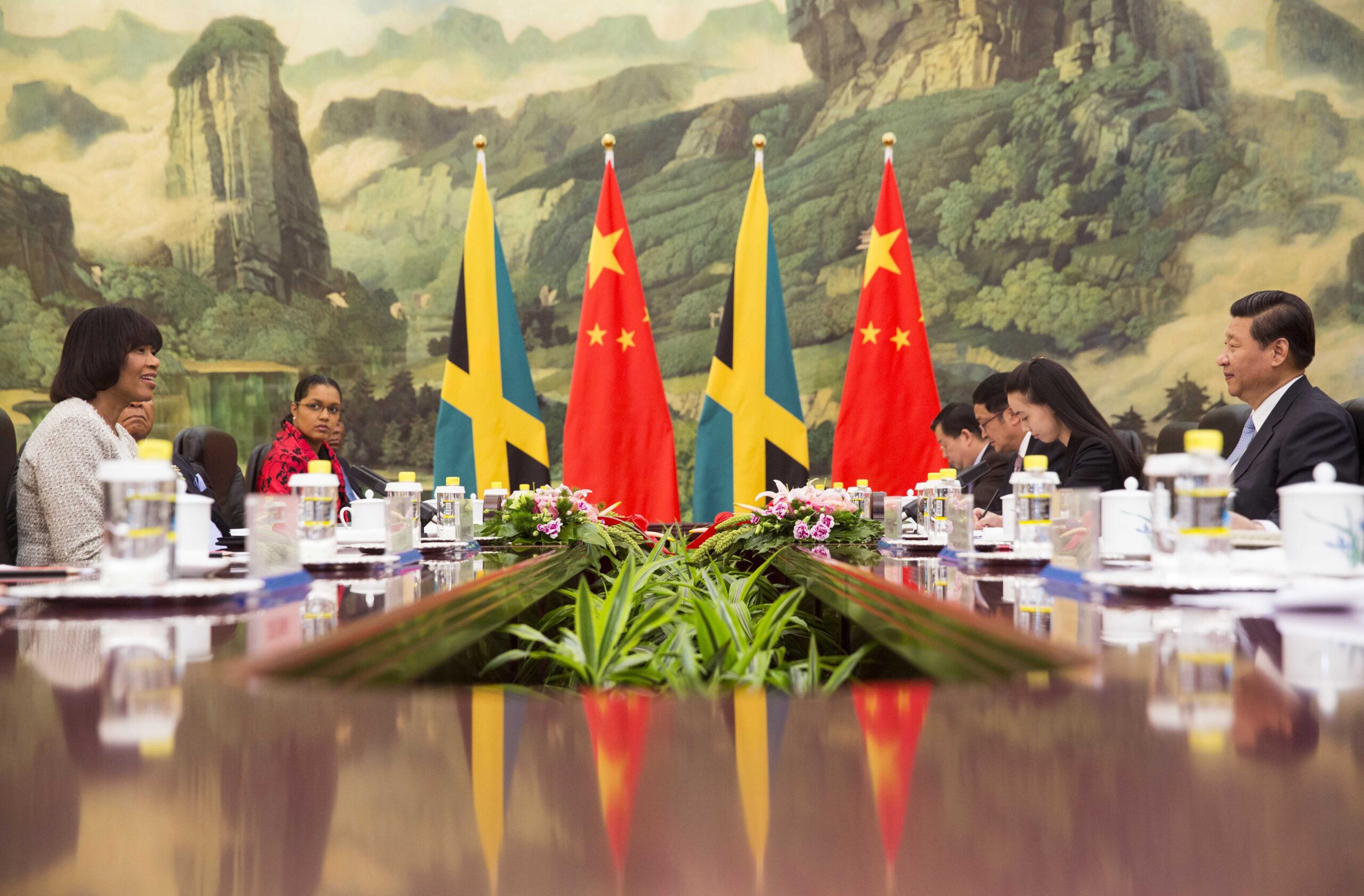

Since 2005, Beijing, under Xi’s presidency, has “invested more than £685bn across 42 Commonwealth” nations. In the Caribbean, by example, Beijing heavily targeted Barbados before the island nation became a republic in November 2021. In the lead up to its end as a realm of Queen Elizabeth, Xi awarded Bridgetown with over £500m in investments – while King Charles, possessing no purse of his own, then as Prince of Wales, could only apologise for England’s “appalling atrocity of slavery.” Similarly, Xi is targeting Jamaica with Kingston thus far netting over £2.6bn.

Xi’s investments, however, are neither altruistic, nor merely economic. They come attached with harsh mafia-like loan-shark repayment terms and conditions, even if it means recipient governments looking the other way when it comes to human rights and the principles of democracy.

In 2020, when China was under siege by the UK over its draconian Hong Kong National Security Law at the 44th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council, Beijing’s foreign ministry enforcers called in their chits. 53 members backed Beijing including, disconcertingly but not surprisingly, two of King Charles’ Commonwealth realms, Antigua and Barbuda and Papua New Guinea.

Despite the alliance’s central founding principle of “improving the lives of people,” ten other Commonwealth member states, alarmingly but not unexpectedly either, supported Beijing over London: Cameroon, Gabon, Gambia, Lesotho, Mozambique, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Togo, and Zambia. Money talks – especially Xi’s. It is also silencing or relegating members to a second tier or third tier of international influence – including, going forward, King Charles, if left unchecked.

In European football fixture terms, it was China 1, UK 0.

Beijing’s morally abhorrent and subversive win, not only struck at the heart of the Commonwealth Charter and its principled mandate to be “a compelling force for good,” but it did so by using economic daggers that London and the Bank of England on their own, are hard-pressed to competitively match. In a classic case of, ‘I must pay the rent, but I can’t pay the rent,’ the UK is presently without answers.

The rent, nonetheless, on the Commonwealth is now overdue.

If King Charles’ primacy is to be preserved, UK Prime Minister Liz Truss must urgently adopt creative new defensive strategies to thwart Xi’s hostile takeover bid of the Commonwealth. Deploying a hostile takeover-like ‘Crown Jewel Defence’ is one approach Truss could consider, wherein Whitehall would withhold trade, military aid, and bilateral exchanges with any member state violating the spirit of the Commonwealth Charter in its agreements with Beijing or its diplomatic support of Xi.

Another tactic Truss could consider is becoming a ‘White Knight Defence,’ wherein London, working closely with the largest economies of the Commonwealth, would collectively undertake the same type of infrastructure investments Xi is currently making in poorer member-state nations – including, potentially, creating a ‘Bank of the Commonwealth’ as a counter to Beijing.

It is not an easy decision for Truss or King Charles. Doing nothing, however, will come at an even greater cost to Queen Elizabeth’s Commonwealth legacy. Xi is aggressively buying up shareholder ‘common’ shares at a premium, while Whitehall is struggling with how to keep the lights on and being domestically distracted over the debate of whether or not to try and stop its sub-tenants – the 14 remaining realms – from leaving.

London can ill-afford to lose a final shareholder proxy vote. Under Queen Elizabeth’s aegis, the Commonwealth developed into an economic powerhouse and continues to be a global economic colossus in the making, replete with pecuniary staying power, both in terms of people – and rare and vital green technology natural minerals. 32% of the world’s 7.9 billion population reside and work in it – and 60% are under the age of 29.

In 2021, 9.4% of the UK’s economic trade was with its Commonwealth partners, generating a goods and services trade surplus of £2bn trade surplus, £61bn in exports and £59bn in imports. Nearly equal in trade to Germany, 74% of all UK’s Commonwealth trade derives from five member states: India (20.1%), Canada (17.7%), Singapore (13.8%), Australia (11.9%), and South Africa (9.99%).

London’s economic standing within the Commonwealth is continuing to markedly slip when measured in gross domestic product (GDP). India, for the first time, according to the International Monetary Fund, overtook the UK in 2022, generating $3.5tn of GDP versus the UK’s $3.4tn.

Truss, accordingly, in her post-Brexit world, must, in addition to fending off Xi, seek out new and alternative economic catalysts from within the Commonwealth to counter Beijing’s growing global economic influence. Economic bastions do exist, including Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and South Africa – but much more will be needed across the entirety of the alliance. The UK has economically ‘taken’ for centuries, and now must find a way to ‘give back,’ or risk losing London’s standing, and King Charles’ Commonwealth leadership, to Xi.

Encouragingly, as a start, in December 2021, London and Canberra entered into an “historic trade deal” anticipated to generate “£10.4bn of additional trade,” while also “eliminating tariffs on 100% of UK exports. The British government’s official impact assessment suggests the Free Trade Agreement between the UK and Australia will add 0.08% to GDP or £2.3bn by 2035. Two months later, Downing Street agreed to a similar trade deal with New Zealand; Whitehall estimates trade with New Zealand will add 0.03% or £0.8bn by 2035.

In December 2020, London entered into a Free Trade Agreement with Singapore after the UK’s withdraw from the EU. Significantly, the agreement provides the UK with access to reduced or tariff-free supply-chain trade with the entirety of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) when transacting through Singapore as an intermediary.

Beijing notably, however, had already beaten the UK and the US to the punch in the Pacific. In November 2020, China preemptively co-opted ASEAN, by backing the formation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) around the economic alliance to create the “world’s largest free trade block.” Signed in Hanoi, RCEP leaves London and Washington on the outside looking in – and comprises the ASEAN member states, China, and notably, the Commonwealth realms of Australia and New Zealand.

Now, more than ever, London and Washington must view Xi’s global actions in totality – and not merely regionally or narrowly. In that vein, Beijing’s hostile economic takeover attempt of the Commonwealth is just one of many moving parts of far grander and economic and military designs.

For instance, China is dominating the supply and production of rare earth elements (REEs). Composed of 17 elements with exotic names such as cerium (Ce), neodymium (Nd), and lutetium (Lu), REEs, once refined, are vital in the production of magnets, lights, LED screens, glass, laboratory catalysts, batteries, and steel alloys.

Of the world’s known 120,000,000t reserve of REEs as of December 2021, China controls 36.7% or 44,000,000t compared to virtually nothing in the UK and only 1.5% or 1,800,000t in the US. India leads the Commonwealth with 5.9% or 6,900,000t, followed by Australia at 3.3% or 4,000,000t, Canada at 0.69% or 830,000t, Tanzania at 890,000t or 0.74%, and South Africa at 790,000t or 0.66%.

Other acts of Chinese economic subversion are darker and more nefarious – and largely military in design. Examples include Beijing’s recent trade deal with the Solomon Islands, and, to some extent, in Myanmar also, given the decision in August 2021 by Beijing to fund the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone and deep-sea port project as a key strategic component of BRI.

The Jacobite, in the form of Xi, have landed again – 276 years later; if Queen Elizabeth’s crowning achievement is to survive, then Truss must consider standing up a well-funded and well-armed Commonwealth version of the Vigil of the Princes under the symbolic aegis of King Charles. If not, Beijing Ltd’s hostile takeover attempt of the Commonwealth might well succeed – with Xi as its CEO.