China will launch a manned lunar mission within seven years and plans to become the first country to establish a base on the Moon – a move which will make it a front runner in the increasingly congested space race.

Beijing has increased its space budget to around £16bn a year – although the exact figure could be much higher – placing it second only to the US in terms of investment.

A recently declassified US national security report also found that China is set to lead the world in space by 2045.

The report released by the US Director of National Security, states: “China is steadily progressing toward its goal of becoming a world-class space leader, with the intent to match or exceed the United States by 2045. Even by 2030, China probably will achieve world-class status in all but a few space technology areas.”

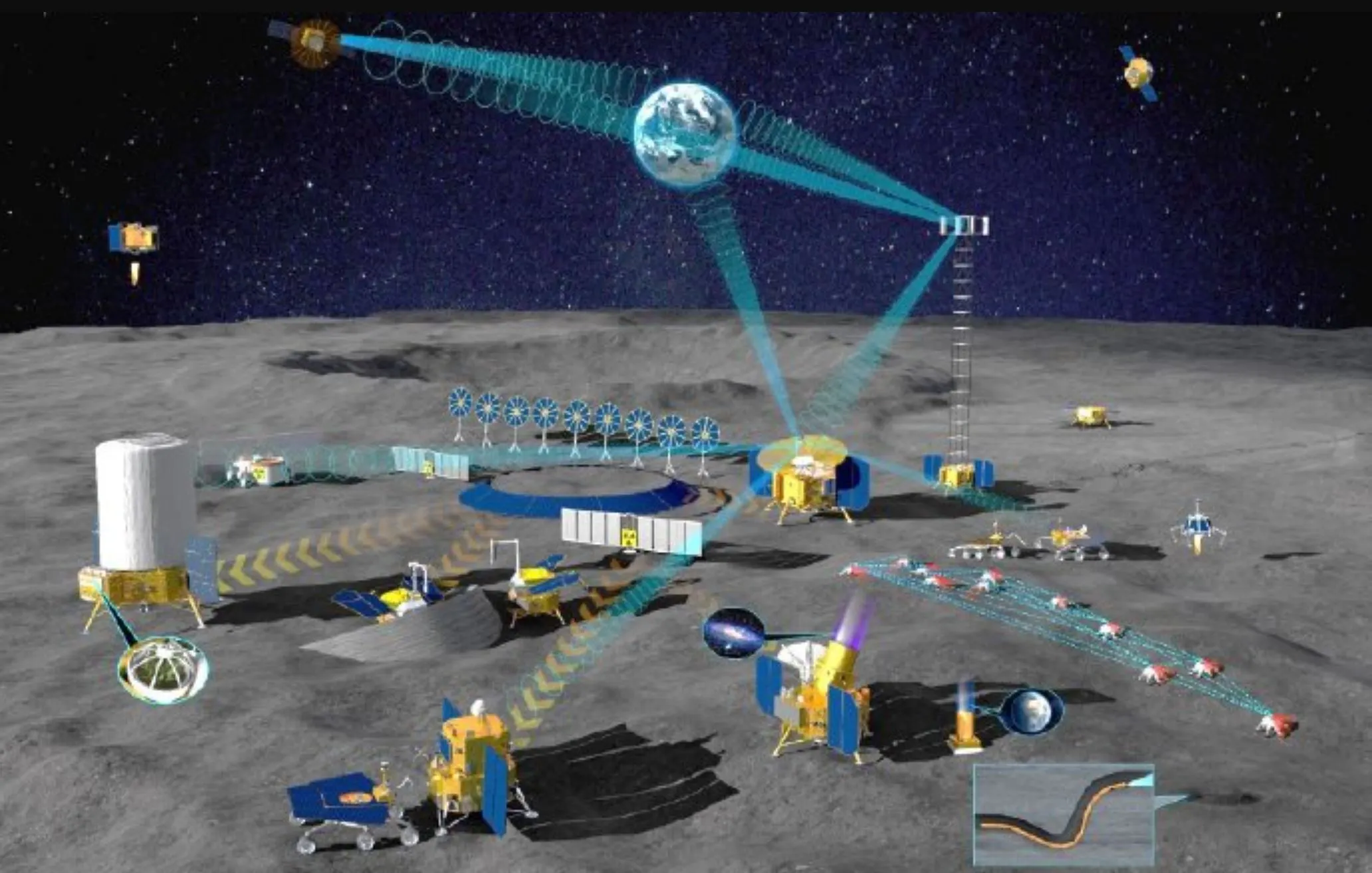

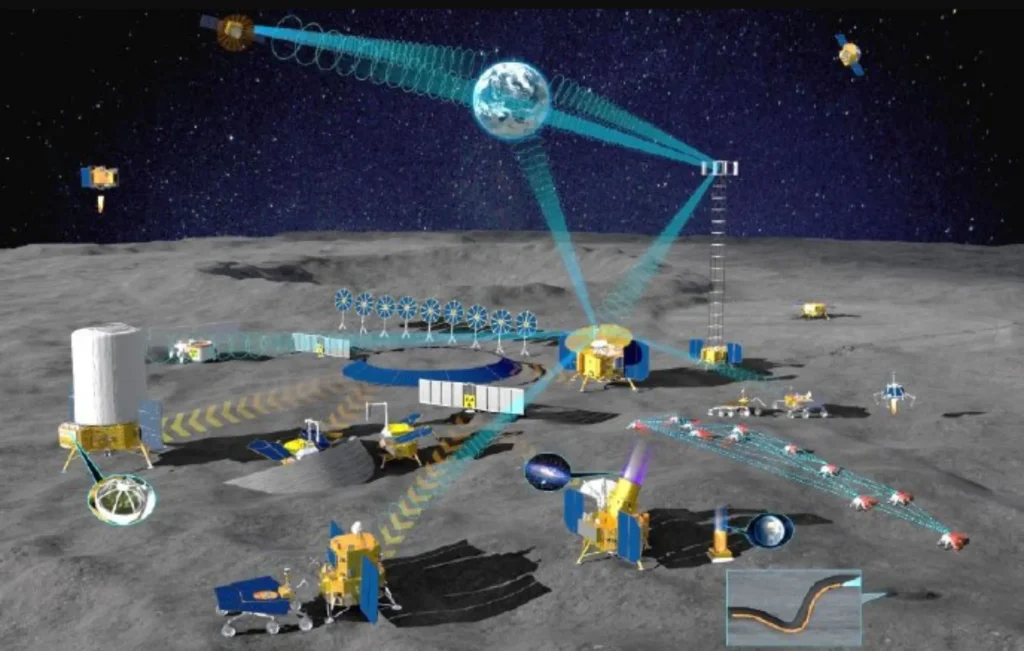

Graphic of China’s Planned Moon Base Credit: CNSA

The disclosure has led to fears that China may attempt to colonise vast areas of the Moon and warn other nations to stay away.

Global interest in lunar missions resurfaced last week after India became the first country to land a craft in the Moon’s south pole.

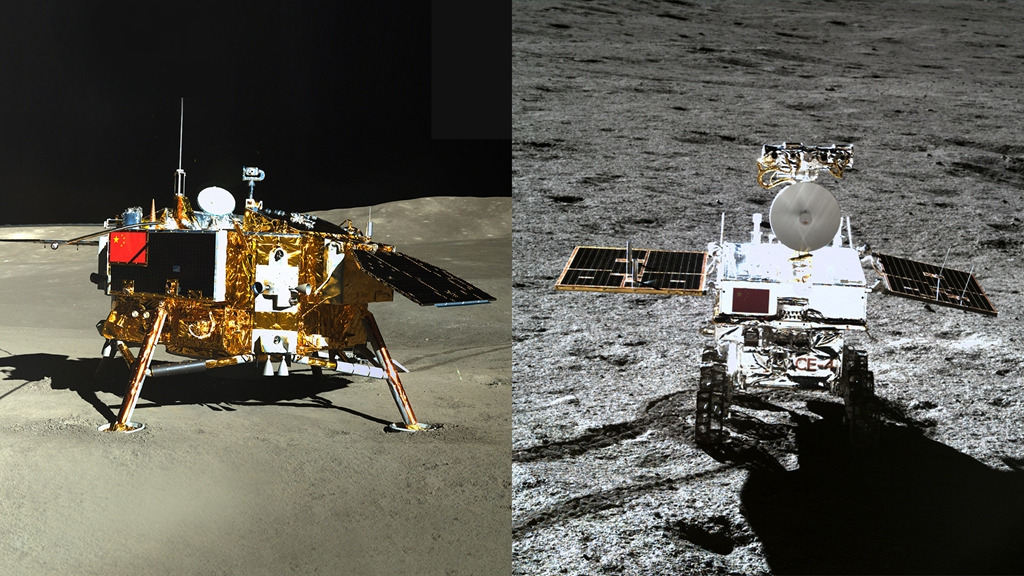

But China has had a robotic rover – Yutu-2 – moving around the Moon’s far side for the past four years, collecting data and analysing rock samples in preparation for future missions.

China’s Yutu-2 Credit: NASA

In the years since the launch of the Chinese Chang’e 4 mission in 2018, the People’s Liberation Army has also spent billions on lasers, anti-satellite and hypersonic missiles, and space-to-space orbital engagement weapons.

Over the same time frame, the Tiangong Chinese Space Station also became operational, in 2021.

China has also stated that it plans to have a base on the Moon by the 2030s.

Beijing announced earlier this year that Russia, Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, and the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization (APSCO) have signed agreements to engage in the International Lunar Research Station.

The Chinese space agency has claimed further ten countries and organisations are currently negotiating agreements.

Nasa Administrator Bill Nelson has already warned that China could attempt to aggressively colonise sectors of the Moon.

Earlier this year, he warned: “It is a fact: we’re in a space race. And it is true that we better watch out that they (China) don’t get to a place on the moon under the guise of scientific research. And it is not beyond the realm of possibility that they say, ‘Keep out, we’re here, this is our territory.”

Terry Virts, a former commander of the International Space Station and Space Shuttle and a retired Air Force colonel, said the competition with China has political and security components.

“On one level, it is a political competition to show whose system works better,” he said in an interview. “What they really want is respect as the world’s top country. They want to be the dominant power on Earth, so going to the moon is a way to show their system is working. If they beat us back to the moon it shows they are better than us.”

But space exploration is a costly business requiring vast and long-term investment.

From 2012 through to 2028, NASA will have spent an estimated US$102.5bn on the Artemis programme – the US and multi-agency mission to return astronauts to the Moon – although that figure will undoubtedly rise.

One of Artemis’s aims is to land the “first woman and first person of colour on the surface of the Moon”, to explore the lunar surface, and lay the groundwork to send astronauts to Mars.

In 2021, the US’s space budget was roughly US$59.8bn and while China has been investing heavily it had an estimated budget of US$16.18bn, less than a third of the US budget.

In terms of missions, China attempted 55 orbital launches, four more than the US’s 51 and while the total numbers may be similar, but the rocket’s payloads were very different.

Up to 84 percent of Chinese launches had government or military payloads intended mostly for electronic intelligence and optical imaging.

By comparison, 61 percent of US launches were predominantly for Earth observation or telecommunications.

Since the 1990s, the U.S. has worked with 14 other nations, including Russia, to operate the International Space Station.

Although large, the ISS is now 24 years old, and participating nations are planning to retire it in 2030.

Meanwhile, China has built and launched all of the different parts of the Tiangong space station and remains the sole operator of the station, despite having invited others to join.

China’s growing presence in space also comes with the inevitable threat posed by the communist state’s history of aggressive espionage and cyber attacks.

China has been accused of attempting cyber attacks on India’s communication satellites in 2017. The attacks were denied by the Indian Space and Research Organisation (ISRO) but it did acknowledge the risks involving Chinese cyber attacks.

New allegations against China-linked cyber-attacks re-emerged again following the failure of the Chandrayaan-2 mission – the forerunner to India’s recent moon landing – in 2019.

Back then, North Korea, one of China’s closest allies, was accused of launching a cyber-attack against the space mission, which ended after ISRO lost contact with the craft.

According to the Financial Times, ISRO was warned of the cyber-attack during the Chandrayaan-2 moon mission in September.

Employees are feared to have opened phishing emails from North Korea hackers accidentally installing malware onto their systems.

But the space agency insisted that its systems had not been compromised by the attempted hacking.

It is not the first time Chinese hackers have been accused of trying to sabotage space missions. In 2007 and 2008, two US satellites fell victim to cyber-attacks.

In 2018, China was again accused of being behind a massive global cyber-attack which resulted in the theft of information from at least 45 US tech companies and government agencies, including NASA, the Navy and the US Department of Energy.