In the third part of our four-part series on the future of the Commonwealth, NSN contributors Jon Sweet. Alan Jenkins, and Mark Toth look at the further growing influence of China across the realms.

In their final public vigil for Queen Elizabeth II in Westminster Hall, King Charles III, Princess Anne, Prince Andrew, and Prince Edward silently stood guard over the former Head of the Commonwealth of Nations. Steeped in royal funereal tradition dating back to the death of King George V in 1936, the sepulchral Vigil of the Princes symbolically underscored the question: should the Commonwealth under the aegis of King Charles mount a vigil in its own defence to guard against Chinese President Xi Jinping – a modern-day Jacobite-type pretender to Queen Elizabeth’s crowning global legacy?

Under Xi’s leadership, Beijing is systematically subjecting the 56-member alliance to a barrage of passive-aggressive military-like assaults, utilising economic tools and debt obligations as forms of time-released weaponry to subvert and, ultimately, to control economically and militarily large swaths of the Commonwealth. Equally portentously, Xi is methodically enveloping much of the alliance in a global military footprint designed to intimidate and, if necessary, to subjugate its member states.

The UK alongside Australia, Canada, India, Singapore, and South Africa – the economic princes of the Commonwealth – are nearing an existential inflection point in the alliance’s history. Either the UK’s Prime Minister Liz Truss or her counterparts collectively acknowledge Xi’s economic machinations are military in design and respond accordingly, or they risk failing jointly as a democratic bulwark against Beijing’s increasingly militant autocracy.

China is not waiting for the princes of the Commonwealth to reach a consensus. Xi’s strategic deployment of tactical economic, socio-political, and diplomatic tools is rapidly changing commercial and military landscapes throughout Africa, Asia, and the Indo-Pacific – and, by calculated design, the Commonwealth as well.

Xi initiated this overarching global initiative by targeting key Pacific shipping lanes once predominantly patrolled and protected by the Royal Navy and the US Navy. These strategic waters run through the Sea of Japan (East Sea), South China Sea, Philippine Sea, Gulf of Thailand, Andaman Sea, Celebes Seas, Java Sea, and Banda Sea, as well as the Commonwealth waters of the Singapore Strait, Strait of Malacca, Timor Sea, Arafura Sea, Solomon Sea, and Coral Sea.

Control of these waters is being challenged by an increasingly hostile Chinese blue-water navy, which significantly has now surpassed the size of the UK and US navies; that is well-supported by a string of newly fortified military islands, air strips, and naval bases with more to come.

In Africa, one of Xi’s initial primary targets, Beijing is focused on monopolising and fully controlling the continent’s supply and production of Rare Earth Elements (REEs), which are essential in the manufacturing of smart munitions and weaponry, green energy, green technology, and hi-tech products. To that end, Beijing has concentrated on developing East Africa as a port and rail terminus for the movement and shipping of REEs and other vital natural resources such as iron back to the Chinese mainland.

Under the commercial guise of the China Merchants Group, Beijing is undertaking a “$3bn expansion” of Djibouti’s century old seaport – East Africa’s optimally located deep-water seaport with preeminent access to the major shipping lanes in the Indian Ocean. This undertaking includes building a separate pier for Chinese naval vessels, including one berth that is large enough for a Chinese aircraft carrier, and a military base to house soldiers to ‘protect’ Xi’s investment and monitor activities of US Forces assigned to the Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) at Camp Lemonnier mere yards away.

Xi’s targeting of East Africa also includes the Commonwealth. China has begun construction of another deep-water port in Lamu, Kenya for $23bn as part of a larger Lamu Port South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor. The end state is clear – extend Beijing’s economic tentacles into Kenya, an important Commonwealth nation, and elsewhere in the alliance. Beijing is also, purportedly, targeting Tanzania to build a military base.

By financing and building the coastal and interior infrastructure connecting Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan, including ports, rail networks highways, pipelines, and bridges, not only is China extending its China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) into the heart of Africa – and brazenly into the Commonwealth – it is using these economic projects to fuel its growing diplomatic influence and subjugation of large swaths of the African continent.

Beijing’s other Commonwealth targets in Africa in addition to Djibouti and Kenya, include Cameroon (timber), Gabon (manganese, timber), Ghana (manganese), and South Africa (chromium, manganese) – and, increasingly, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia (all rich in copper, iron, gold, manganese, and other base metals and REEs). China is not only buying the resources, but they are also building the mines, using Chinese labour, overseeing mining operations, and are reaping most of the economic rewards at Africa’s expense – and, additionally, the military rewards in terms of the natural resources needed to produce modern weaponry and smart munitions.

For example, Lithium prices nearly doubled in 2022 to $76,700 per ton; copper prices peaked in 2021, rising as high as $10,500 per ton. Not only does Beijing profit handsomely but, by controlling these and other critical minerals and resources, it creates, at least temporarily, a military supply-chain chokehold on the UK, the US, Nato, and the Commonwealth.

By yielding these Commonwealth markets to Beijing, the UK risks unnecessarily diminishing King Charles’ future influence across the African continent. As it is, “China’s 20-year diplomatic march across Africa” is producing alarming results. According to a survey by South Africa’s Ichikowitz Family Foundation, “youths 18 to 24 across 15 African nations see China as the foreign power with the biggest positive impact in their lives,” including, notably, the Commonwealth member state of South Africa.

Monies being invested into East Africa countries are also buying political influence and delivering diplomatic results in international governing bodies, including from the Commonwealth nations – as evidenced by voting on United Nations General Assembly resolutions. Alarmingly, between 1971 and 2017, Commonwealth members Pakistan voted 91% in agreement with Beijing, Brunei Darussalam 91%, Bangladesh 90%, Namibia, 90%, Sri Lanka 89%, and Malaysia 89%.

Consequently, China’s “Africa Alliance is shifting the world order” – and that of the Commonwealth and its member states. This was in stark evidence earlier in March, when only 51% of African countries voted for the resolution condemning Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine. 17 African countries, including the Commonwealth nations of Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda voted to abstain, with Cameroon not voting. Beijing’s capacity to protect Putin in the UN extended across Africa and, unacceptably, deep into the African Commonwealth member states.

Most recently, 10 Commonwealth nations abstained voted against the October 12th UN resolution condemning Russia’s annexation of the Ukrainian oblasts of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia and calling for their reversal — including, India, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Togo, Uganda, and Tanzania. Cameron, once again, did not vote, nor as an aside, notably did Djibouti. Xi’s influence, particularly in Africa, remains potent and ongoing.

Beijing, militarily, fully recognises the growing economic and political advantages China is accumulating – especially in the Commonwealth. Xi is building up a powerful global military presence, thereby enhancing his ability, if needed, to exert force in order to retain them.

Ports are ‘protected’ by Chinese soldiers, and China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy secures the shipping lanes, including militarising islands strategically positioned along the route back to mainland China. These islands are armed with anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems, laser and jamming equipment and fighter jets, all positioned to ensure the natural resources extracted from Africa and Commonwealth countries make it to their destination: mainland China.

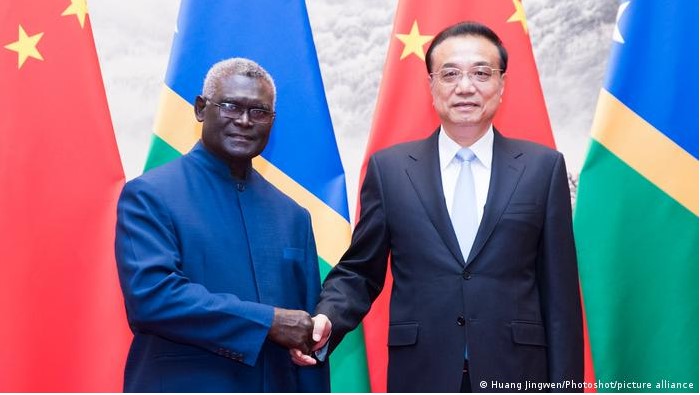

Xi is implementing the same approach throughout the Indo-Pacific, including targeting the Commonwealth nations of Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. As an example, Beijing is constructing a naval base in Cambodia aimed at the Istana in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur.

In April, however, Beijing went one ‘naval base too far,’ by signing a security agreement with the Solomon Islands that contained a provision for the construction of a Chinese naval base. The then Australian Minister Scott Morrison quickly drew a redline, ending Beijing’s military machinations for now.

Comparatively, the military threat to the Commonwealth in the Caribbean is minor compared to that in Africa or the Pacific; however, it exists, and it is Moscow that is largely responsible. Republican tensions and lingering post-colonial and anti-slavery resentment against the UK present opportunities for republican mischief. Further, Moscow has renewed flights in recent years by aircraft from its Long-Range Strategic forces to Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, raising the spectre of a modern-day Cuban Missile Crisis.

When added to the recent transition by Barbados to become a republic and the declared intention by Jamaica to follow suit, there are storm clouds over the Caribbean that are not just associated with the hurricane season. The recent royal tour of the Caribbean by King Charles’ son and heir, William and his wife Catherine, was buffeted by protests throughout and presages a possible domino effect of republicanism.

While these storm clouds are chiefly political in nature, they are popular with Caribbean voters and may serve to weaken economic and military ties with the UK if republican sentiment is left unresolved. Similarly, it could also disrupt trade between the UK and the island nations of the Caribbean, already suffering from a dramatic fall-off in tourism, due to the pandemic, which has yet to recover. Xi, as a result, is likely to view this as an additional opportunity to sow discord within the Commonwealth and in the US’ backyard just as the Soviet Union once sought to do in Cuba, while China seeks to extend its influence in the Caribbean and Central and South America.

Globally, Xi’s brand of autocracy – ‘democratic dictatorship’ – is militantly challenging western democracy and his intent is to marginalise, if not displace democracy and the UK, Nato, and the US in the process. Part and parcel to Xi’s design is subsuming the Commonwealth to economically and militarily weaken the UK and Washington.

If the Commonwealth is to avoid being subsumed by Beijing, then Truss, under the aegis of King Charles must consider reimagining the alliance and extolling the princes of the Commonwealth – arguably, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Singapore, and India – to militarily mobilise against Xi and stand vigil against the modern-day Jacobite. If not, then as the eight-part a cappella composed by Sir James MacMillan CBE for Queen Elizabeth’s funeral service at Westminster Abbey symbolically forewarned, the Commonwealth member states may soon be asking each other, ‘Who shall separate us?’

China and Russia are heavily waging the answer that autocracy can and will economically, diplomatically, and militarily separate the Commonwealth. If they are to be stopped, and Queen Elizabeth’s legacy preserved, then under the symbolic aegis of King Charles with Truss’ guidance, London and the Commonwealth must ask each other, ‘Who among us shall lead?’