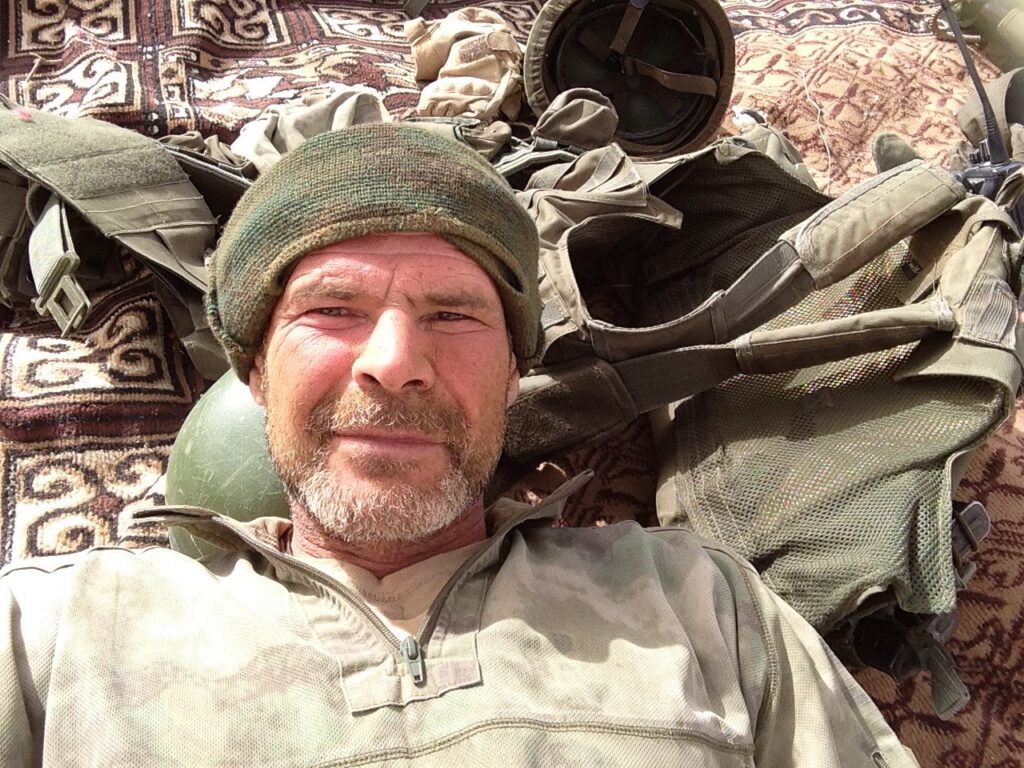

Marat Gabidullin chooses where he sits carefully, settling on a sofa with a clear line of sight to the nearest exit. His dark eyes constantly dart back and forth as he recalls his past life.

Before he arrived on the French Riviera, where he is seeking asylum, Gabidullin was a right hand man for President Putin’s personal warlord, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the founder of the Wagner group which has an unenviable reputation for brutality.

“Prigozhin is a very dangerous man who should not be underestimated,” says the 56-year-old, who worked for Wagner in St Petersburg after fighting for the group in Syria, where it has been accused of atrocities as part of the Kremlin’s support for the Assad regime. “He is unique. He is very ruthless, very bright and thinks on a much larger scale than other people. He can be charming, he can be rude.”

Prigozhin, 61, is regularly summoned by Putin for private talks and is now seeking to build his own power base in politics, says Gabidullin, a convicted killer jailed in 1994 for shooting a criminal before he joined the mercenaries.

A former paratrooper, he was unable to rejoin the Russian army because of his criminal record. Before being accepted as a mercenary he had to pass a routine lie-detector test designed to weed out crooks seeking access to weaponry.

For now, adds the fighter who fled Wagner in 2019, Prigozhin will be content to act as “guard dog” to Putin and is not plotting a bid to succeed him.

Putin will not hesitate to destroy Wagner the moment it threatens him, Gabidullin says. “The action which is needed to erase this Wagner Group would take only two days,” he says. “For Putin it is enough just to click and they will not exist any more.”

Asked whether Prizoghin could replace Putin, Gabidullin told National Security News and The Times newspaper: “He is not going to be able to become president because he doesn’t have the power base to become a president. So he is in active search of people to create a political union. Probably he is going to try to take the place of Zhirinovsky. He definitely has political ambitions.”

Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a veteran ultra-nationalist and showman of Russian politics who predicted the invasion of Ukraine almost to the day, died in April, aged 75. The leader of the far-right Liberal Democratic Party for 30 years had been dubbed as “Russia’s Trump”.

It is Putin who most often initiates conversations with Prizoghin, but Gabidullin suggests that there is little trust between the two, despite their long-standing relationship. “In that environment, can there be any friendly relationship? Prizoghin is a kind of a helper for Putin. They are dangerous, both of them, for humanity.”

He now compares Wagner to the Oprichnik, the secret police of Ivan IV, who ruled from 1547. The Oprichnik dressed in black robes with the insignia of a severed dog’s head and rode black horses.

They quelled dissent through intimidation, beating and ritual executions, boiling the Tsar’s opponents to death and tearing them limb from limb with horses. Gabidullin said Putin was using the mindset of Russian people “that we don’t learn from our history. People don’t want to make any conclusions from our historic lessons.”

“In Russian history there is some kind of precedent, the Oprichnik of Ivan IV. They were having the same kind of functions to basically push down the political opponents and guard the throne. The Oprichnik left a bloody trail in our history.”

Prizoghin’s own cruelty was most recently demonstrated when he rejoiced at a video depicting the murder of Yevgeny Nuzhin, 55, a Wagner Group member who defected to Ukraine.

In footage shared online Nuzhin could be seen with his head taped to a piece of masonry as he explained he had chosen to “fight against the Russians”. After Nuzhin finished speaking, a man was seen to strike him on the side of the head and neck with a sledgehammer and then deliver another blow to his head as he slumped to the floor.

Prigozhin said the video demonstrated “wonderful directorial work and can be watched at a single sitting”. Gabidullin said Prizoghin’s apparently delight at murder was an attempt to reinforce his authority. He said it was “to show that they have their own laws that are higher than any laws”.

“It’s a kind of message sent to everybody, to traitors, advertising the possibilities of how they can do things.”

Despite having achieved notoriety for their alleged atrocities in Syria and Africa, Gabidullin said the Wager mercenaries are now becoming angrier and more lawless as the battle grinds on in Ukraine.

A simple recruit on training receives £1,000 a month, a mercenary in a war zone £2,000, if he sees active duty £3,000. Officers were paid more. Successful missions like the capture of Palmyra from Islamic State in Syria were rewarded with an individual bonus of £9,000 for the ranks rising to £25,000 for a commander. Compensation was paid for injuries or death.

The Wagner Group operates outside the law, Gabidullin explains. Unlike the police or the FSB, the internal security service which succeeded the KGB, it lacks a formal legal status. This gives it greater freedom of manoeuvre and an impunity from accountability. “Wagner is a symptom of the disease infecting Russia”, says Gabidullin.

“Other countries need to be aware that this is what happens when democracy breaks down. You end up with Wagner – a private military company which has become a tool of the Russian state.”

The Ukraine war is attracting a variety of mercenary groups besides Wagner. The Redoubt outfit can be compared to Wagner in terms of experience having also fought in Syria, Gabidullin says. Another private army calls itself “Kazaki” (Cossacks). Gabidullin said these rival mercenary groups lacked the bureaucracy and bases which make Wagner effective.

Wagner is enlisting prisoners to go to war in Ukraine because its best men are required for more far-flung operations, Gabidullin claims. “Prigozhin is not going to put into the war people who are veterans who are staying with him. Wagner needs them in Africa or Syria. The Russian state mindset is that you can put criminals at your power, at your service. Their life is not worth anything.”

Gabidullin’s memoir, The Same River Twice, came out in Russia and has been picked up by a French publisher. He observed Prigozhin at close quarters when he was posted as an assistant at the Wagner Group’s head office in St Petersburg in 2017. The Wagner chief “is absolutely sure that he is always right. There can be no objections. Fear was in the atmosphere inside the office,” he says.

The ex-mercenary feels he is a prime target for assassination, not because of the content of his memoirs but because of the stance he is taking to warn the public about the dangers of the Wagner Group to Russian society.

“The main danger is that Prigozhin is extremely smart and capable. He thinks on a big scale. He is dangerous for Russia itself and for the Russian people and since he is getting the possibility to influence Russian people he also becomes a danger for all the world.”

The use of mercenaries in Ukraine is a sign of how Russian society and its institutions are failing, Gabidullin believes. “In the end our military forces were not ready for the war. In our country if everything had been organised adequately, nobody would have thought of using the Wagner Group in war,” he says. “It would have been the army which should have been fighting.”

He said the Wagner Group was tougher than the Russian army because its members are veterans of active service: “They have a better basis because they have seen real military action.”

He adds: “My story is a warning to the West — don’t let this happen to you.”