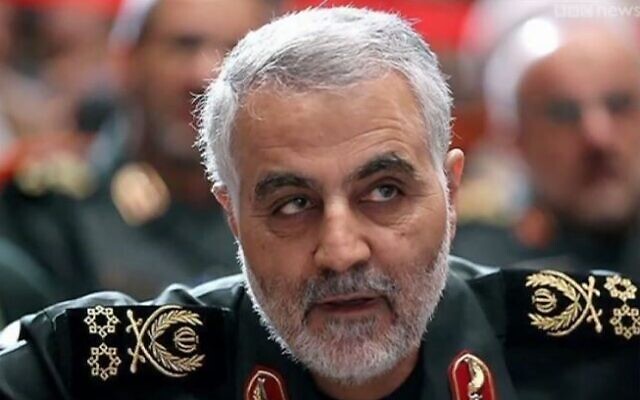

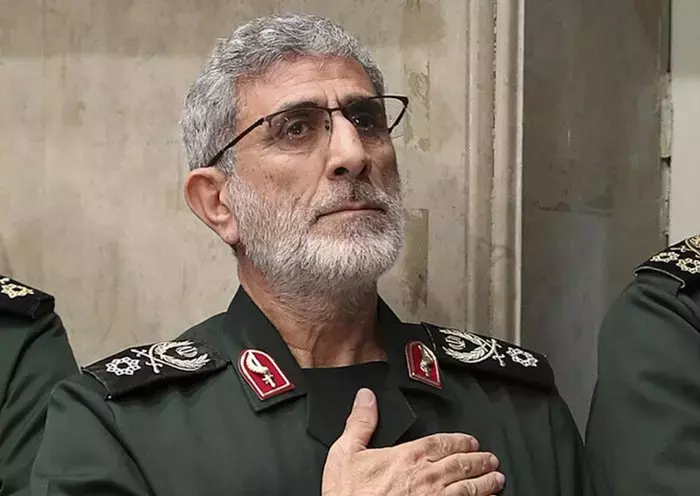

Profile on Brigadier General Esmail Qaani, the commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps Quds Force.

The CIA assassination of Major General Qasem Soleimani, the commander of Iran’s notorious Quds Force, in a drone attack in 2020 was designed to send a message to Iran’s most powerful leaders.

Washington wanted Tehran’s ruling elite – those religious leaders and military chiefs responsible for exporting Shia terrorism around the Middle East and across the world – to understand that for them nowhere was safe.

Soleimani’s death was public, dramatic and sent shockwaves across the Islamic republic. Within minutes of his demise, the attack, and what was left of Soleimani’s shredded body, was being broadcast around the world on TV screens and via social media.

Within 24 hours of Soleimani’s death his deputy of more than 25 years, Brigadier General Esmail Qaani, became the Quds Force’s new commander. He was the obvious and probably the only real choice to continue the development of what have now become known as Iran’s proxy forces.

But the two men could not be more different. While Soleimani was effectively a celebrity and a national hero, Qanni was largely anonymous, a background figure whose primary responsibilities as second-in-command centered around Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia. Essentially, he looked after the day-to-day running of the organisation, while Soleimani became the public face of the Quds Force.

As Quds Force commander, Soleimani was the most powerful figure in Iran, second only to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Islamic Republic’s supreme leader.

Khamenei had described Soleimani as a living martyr and at his funeral so many Iranians turned up for the procession that 50 died in the crush.

Soleimani’s life’s work was the creation of the series of regional militias allied to Iran in various degrees and what have now become known as the “axis of resistance”.

Soleimani’s highly secretive Quds Force – an organisation akin to the CIA and the US special operations group according to former US General Stanley McChrystal – had trained, equipped and financed terrorist groups from Hamas in the Gaza, Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen. He also sent troops into Syria to assist President Bashar Al-Assad in crushing the loose coalition of armed opposition groups – including the Islamic State.

The funding of the terror network, as has previously been reported by National Security News, has cost Tehran over 16 bn USD since 2012.

In the four years since taking over as the Quds Force commander, Qanni has remained largely in the shadows, but the axis of resistance now finds itself at the centre of a global storm following a series of regional military escalations which emerged in the wake of the October 7th Hamas attack on Israel.

So what is known about Qanni? Unlike many senior figures within the Iranian hierarchy, Qanni was not directly involved in the 1979 revolution, which saw Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Iranian Shah, deposed and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini installed as the supreme leader of Iran.

In a rare autobiographical interview published in the October 2015 edition of the news journal Ramz-e Obour, he admitted he did not play a prominent role: “I was present [in the revolution] like the rest of the people.” Just as remarkably, he admitted he did not join the ranks of the revolutionaries right away—instead, he enlisted with the local branch of the nascent IRGC in his native Khorasan region in March 1980, a full year after the revolution, but a few months prior to the Iraqi invasion.

Qanni served in the Iran-Iraq War where in 1982 he met Soleimani. In the same interview he added: “We are all war kids. What connects and relates to us, and our camaraderie, is not based on geography and our hometown. We are war comrades, and it was the war that made us friends…Those who become friends at times of hardship have deeper and more lasting relations than those who become friends just because they are neighbourhood friends.”

Qanni took part in several campaigns against the Iraqi army which met with both success and disaster. It was during this period that he also met Ali Khamenei, who at the time was the Iranian president.

Immediately after the war Qanni was promoted to deputy chief of the IRGC Ground Force but it remains unclear when he actually joined the Quds Force. Soleimani probably appointed him as his deputy upon taking leadership of the force sometime between 1997 and 1998.

Today, however, Qanni finds himself at the very centre of what the U.S. government calls the most volatile situation in the Middle East in decades.

The axis of resistance which has been fed and watered by Iran for decades now has the potential to inflame the entire region in a conflagration which erupted in the wake of the Hamas October 7th attack.

Either by fault or design, Iran’s proxies – from the Houthi militias attacking international shipping in the Red Sea, to the attack on an American base on the Jordanian Syrian border which left three soldiers dead – the United States is gradually being drawn deeper into the crisis.

When the US assassinated Soleimani four years ago it was in part to pay for the reported thousands of deaths he was accused of being responsible for. It was also an attempt to derail Iran’s growing influence in the Middle East using proxy militias following the departure of most US troops from the region.

While that may have been achieved, Soleimani’s death may have also led groups such as the Houthis and Hamas to become more independent and less willing to follow Tehran orders.

The Houthis in Yemen are a good example. While they might be equipped and funded by Iran, they regarded themselves as an independent organisation and not a proxy.

Similarly, the Iran-backed groups established in Iraq in recent years all operated within an overall framework established by Tehran, but with the autonomy to pursue their own domestic agendas. The groups’ growing self-sufficiency relieved Tehran of some of the economic burden of financing them, but also lessened its ability to restrain them.

This is exemplified by the fact that Iran-backed militias have carried out more than 196 missile and mortar attacks on US bases in recent months. It is improbable to believe that every attack was sanctioned by Tehran.

While Soleimani used his charisma to mobilise his axis of resistance, Qaani has sought to tie Iran’s disparate allies closer together at an operational level Arash Azizi, the author of a biography on Soleimani, said that is especially true for the Iraqi militias, perhaps the most volatile of all the pieces in the Quds Force network.

He told the Wall Street Journal: “Soleimani had built a relationship with them over the years and was respected by them tremendously,” he said. “Qaani lacks the charisma and history of relationship with these Iraqi and other Arab groups…As a result, Qaani struggles much more in keeping the Iraqi groups in check and in line with the broader axis. Same problem exists in relation to Houthis who are more independent-minded.”

Now it appears Qanni’s main role is to advise the groups the Quds Force has spent years nurturing to proceed with caution.

It has been reported that after the drone strike in Jordan, Iranian officials traveled to Iraq to tell its allies there that the attack had crossed a line by killing American troops. Also, U.S. officials say they have yet to see evidence that Iran ordered the attack, claiming that Tehran would gain nothing by killing American troops.

The mood music suggests that Iran has no real interest in widening the conflict and dragging in the US. The big question is will Qanni be able to get all the non-state actors in the region to dance to his tune?