By Sean Rayment

Japan is rapidly increasing its cybersecurity capabilities through new legislation, international partnerships, and training schemes, following an escalation of threats from hostile states and criminal groups.

The initiative has prompted a meeting in Tokyo between the country’s Defence Minister, Gen Nakatani, and his Lithuanian counterpart, Dovile Sakaliene, during which both sides agreed to deepen cooperation on cybersecurity.

As part of the agreement, a Japanese defence ministry expert will be dispatched to Lithuania in June to learn from the Baltic nation’s cybersecurity specialists, who are widely regarded as among the best in the world due to their experience in countering persistent Russian digital threats.

This agreement follows Tokyo’s announcement earlier this month that it aims to increase the number of specialist cybersecurity technicians from 24,000 to at least 50,000 by 2030. The government unveiled the plan after a panel under the industry ministry indicated that the country requires a cybersecurity workforce of approximately 110,000 skilled professionals.

Demand is expected to continue rising as new regulations will require, from 2026, that the government inspect private companies’ cybersecurity measures — and potentially withhold state subsidies from firms that fail to meet the required standards.

In May, Japan’s national legislature, the Diet, passed legislation introducing the concept of active cyber defence. The new law permits the government to gather communications data in order to defend against digital attacks. It enables authorities to monitor the internet, collect and analyse communications information, and target servers launching cyberattacks — even during peacetime.

Opponents of the legislation have argued that it enables the government to use collected data in criminal investigations, breaching citizens’ privacy. The government has dismissed these concerns, stating that a new oversight panel will be established to ensure accountability.

Ryo Hinata-Yamaguchi, associate professor at Tokyo International University’s Institute for International Strategy, said the challenges posed by increasingly sophisticated cyberattacks from both state actors and criminal groups had “been overlooked for too long”.

“These measures have already been taken in other countries — even in quite liberal places like Europe — but the Japanese government has always said it would be hard to do for privacy and other reasons,” he told This Week in Asia. “But that has meant that Japan’s cyber infrastructure has a lot of vulnerabilities. We just did not pay enough attention to this before. There haven’t been enough laws, and now there aren’t enough people with the necessary skills and experience,” he said. “And that goes for the private sector as well as government agencies.”

The consequences, he added, are already serious.

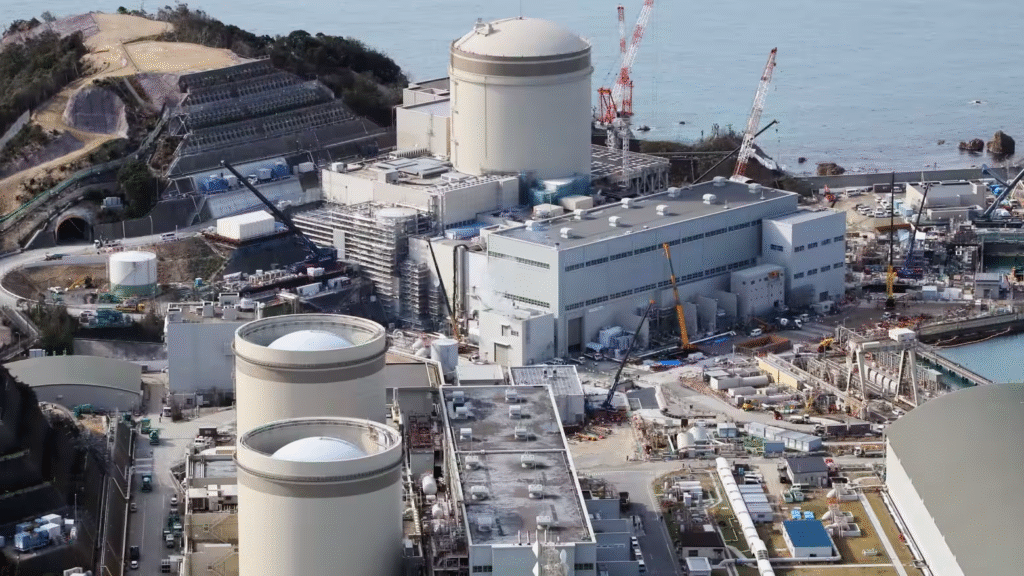

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries’ (MHI) Nagoya plant — where the company designs and builds missile guidance and propulsion systems — was reportedly a specific target. Its Nagasaki shipyard and a facility in Kobe where it builds submarines and nuclear power plant components were also compromised.

At the time, the defence ministry insisted that no sensitive information had been accessed, though it did not name the source of the attack. Reports have suggested that Chinese language was found in the malware script during the investigation.

In 2013, data on 22 million Yahoo Japan users was leaked through unauthorised access. A year later, Japan Airlines suffered the loss of data on 190,000 members of its frequent flyer programme. In 2018, hackers gained access to the internal systems of Japanese cryptocurrency platform Coincheck for more than eight hours, stealing an estimated 58 billion yen (US$443.2 million). Japanese and US law enforcement later concluded the attackers were North Korean operatives — making it the largest single cryptocurrency heist at the time.

Japan’s recent decision is also likely to have been influenced by a string of high-profile incidents involving China and North Korea. These include the breach of SK Telecom’s internal systems in June 2022 — though the attack wasn’t discovered until April 2025. The hack, blamed on Chinese operatives, resulted in the theft of 9 gigabytes of sensitive personal data from around 25 million subscribers.

“These attacks can affect any sector, but the government’s primary concern is defence, the police, public infrastructure, and so on,” Hinata-Yamaguchi said.

“This is not something that can be blamed entirely on North Korea and China, as there are also criminal groups and domestic hackers in Japan. But that just goes to show that threats can come from anywhere — and Japan does not currently have the manpower to fight this. It should have been done before, but now it is overdue and absolutely necessary.”