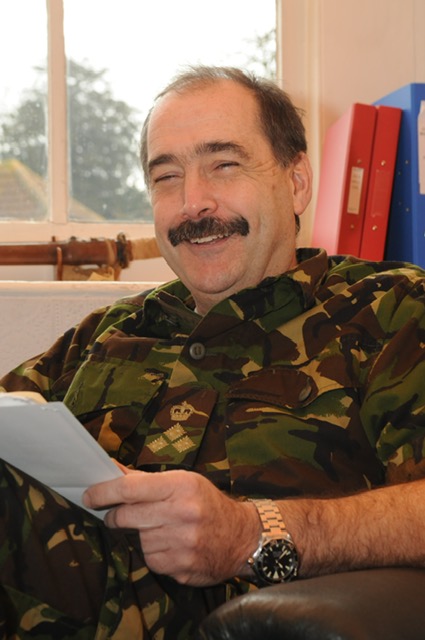

ONE LAW FOR THEM? Are the SAS victims of a witch hunt? Brigadier (Retd) Phil McEvoy OBE, a former head of Operational Law in the British Army, gives his view

On 06 February 2025, Northern Ireland’s Presiding Coroner, Mr Justice Michael Humphries concluded that the deaths of four members of the Irish Republican Army, killed by British forces at Clonoe on 16 February 1992, was as a result of excessive force and was “not reasonable”. In the cases of the deaths of all four IRA gunmen, the coroner said that the use of lethal force was not justified.

His findings attracted mixed reactions; the relatives of those who died claimed a victory in their fight for justice; others, most notably Unionist politicians, have claimed the finding “beggars belief” and is “ludicrous”. So far, there has been no formal response from the Ministry of Defence or from servicemen, especially those involved in the incident. One former serviceman and former MP and Veteran’s Minister, Johnny Mercer, described the finding as “absurd” and a “farce”. Although Mr Mercer is not a lawyer and it is unclear whether he attended the inquest, this sentiment is likely to be shared by many serving and former servicemen.

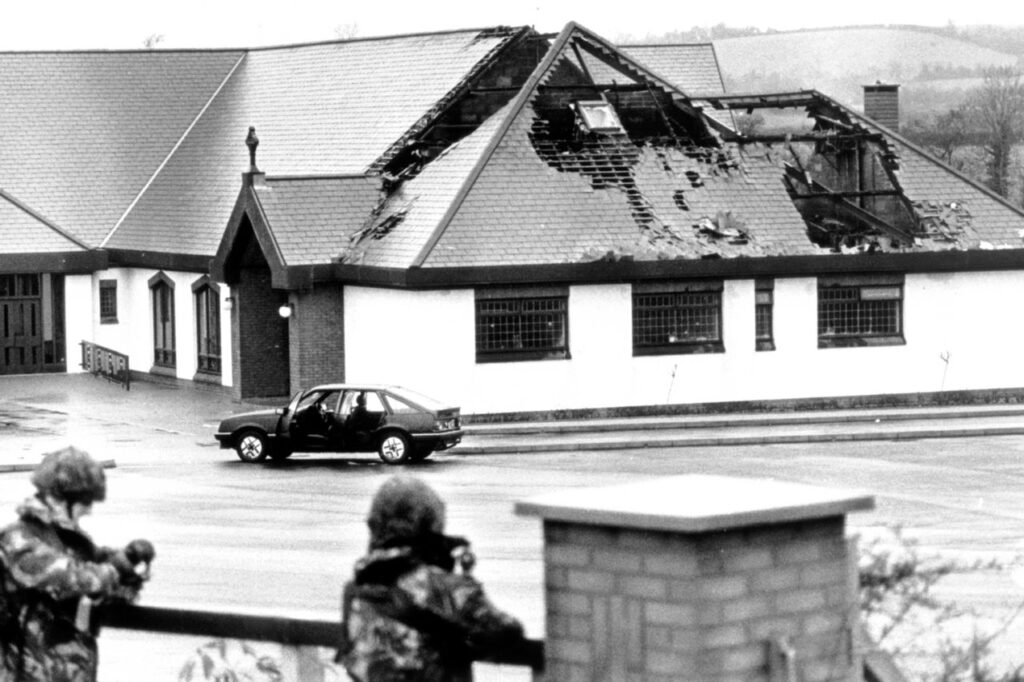

The circumstances of the events of the night of 16 February 1992 can be summarised as follows. An IRA unit had mounted a heavy machine gun, a Soviet made DshK, onto the back of a stolen lorry. The vehicle was driven to the Royal Ulster Constabulary security base in the centre of Coalisland where the IRA unit opened fire into the base. Four men were directly involved in the attack and, in addition to the DshK, they were armed with AKM assault rifles. The men then fled the scene to a rendezvous’ point in the car park of St Patrick’s Church where their getaway team were waiting. En route in the stolen lorry they passed the home of Tony Doris one of their fellow volunteers who had been shot and killed the previous year. There they stopped and celebrated their success by firing into the air and shouting “Up the IRA”. Their celebrations were short lived. Also waiting around the churchyard were soldiers from an undercover unit from the British Army who opened fire, killing the four volunteers; Peter Clancy, Kevin O’Donnell, Sean O’Farrell and Patrick Vincent. It was acknowledged that the volunteers were “on active duty” at the time of their deaths; indeed, a plaque commemorating the four men describes their fate as “killed on active service by British Forces”. In addition to the four men other civilians were present; Three are identified by the Coroner as Aiden McKeever, Kevin Coney and Martin Woods. Two others, identified as CC1 and CC2 declined to give evidence. CC1 was shot and wounded but denied those wounds were inflicted in the car park. CC2 also received a gunshot wound. Both CC1 and CC2 fled to County Monaghan. Martin Woods and Aiden McKeever were shot and wounded. The British soldiers fired approximately 570 rounds. Although the soldiers had claimed that the IRA team had opened fire the coroner, who is also a High Court judge, ruled that this claim was “demonstrably untrue”. In his record of the evidence it is stated that one soldier, Soldier H, suffered a facial injury caused by a bullet from a ricochet from a round fired by another soldier. This account is a brief summary of what was, albeit short, a fast unfolding incident.

In October 1992, the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland made the decision that none of the soldiers involved should face prosecution.

The Coroner’s findings are detailed and thorough. It explains the applicable law, both European and domestic; the security situation in Northern Ireland in 1992; the training given to soldiers on the use of force; the scene where the deaths occurred; the evidence from material witnesses; forensic and medical evidence and finally his findings of fact and conclusions.

The Coroner also addresses the law relating to the use of force including the guidance issued to soldiers – “The Yellow Card”. The law in Northern Ireland, which mirrors that of England and Wales is set out in S3(1) of the Criminal Law Act (Northern Ireland) 1967 which states that;

“A person may use such force as is reasonable in the circumstances in the prevention of crime, or in effecting or assisting in the lawful arrest of offenders or suspected offenders or of persons lawfully at large”.

This is the same law that applies to every citizen and there is no leeway given to the police or military save that Sir Brian Leveson stated in a case involving a police firearms officer that “the examination must be prepared to consider every perspective. These perspectives include a full recognition of the enormous challenges facing the police along with the urgency and almost instantaneous decision making required of the highly trained officers involved”.

The four gunmen were members of the East Tyrone Brigade of the Irish Republican Army. In the 1920’s the IRA adopted a military hierarchy, with Divisions, Brigades, Battalions, Companies and Active Service Units. These formations bear no resemblance in size to British Army formations, but illustrate a command structure with each operation being sanctioned, approved and equipped by higher authority. The East Tyrone Brigade of the Provisional IRA was one of the most active paramilitary group in Northern Ireland conducting numerous attacks on the Army and RUC most notably in Coalisland, Dungannon, Stewartstown, Ardboe and Coagh. In the 1970s their usual tactics were ambushes involving automatic fire, mortars, land mines and IEDs. They were responsible for the deaths of at least 29 members of the security forces and injuring many others. The deaths included those of Pte Eva Martin the first greenfinch to be killed by enemy action and the assassination of 86 year old former soldier and politician Sir Norman Stronge MC and his son, James, at their mansion in Tynan Abbey. The shooting down of a two British Army helicopters in 1974 and 1994 were also attributed, in part, to the East Tyrone Brigade.

It was not surprising therefore that the military authorities and the RUC focussed much of their attention on this Brigade. In 1983 two members of the Brigade, Colm McGirr and Brian Campbell were shot dead by an undercover British Army unit as they approached an arms cache in Coalisland. Later that year Willie Price was shot dead while carrying out an incendiary attack on a factory near Ardboe. In May 1987 the IRA suffered its biggest loss in a single incident in Loughgall where six volunteers were killed by an undercover military unit.

Although Loughgall was a serious dent to the operational capability of the East Tyrone Brigade they, probably in collaboration with other IRA units, carried out further attacks including an attack on a bus carrying British soldiers from Aldergrove to Omagh, at Ballygawly in 1988, killing eight servicemen and injuring thirty six others. Ten days later Gerard Harte and his brother Martin and Brian Mullan were killed in an ambush in Drumnakilly, again by an undercover unit, as the IRA were planning to murder an off-duty member of the Ulster Defence Regiment. There was no let-up in the 1990s, with a pattern emerging. The Brigade were planning attacks on comparatively remote police stations and off duty personnel by means of, small arms, the use of heavy plant machinery loaded with explosives, improvised flame throwers, and vehicle borne bombs. In response, the military tactics were also evolving, with carefully orchestrated ambushes. The military were either incredibly lucky or in possession of accurate intelligence. These ambushes led to the deaths of Lawrence McNally, Michael Ryan and Tony Doris in Coagh 1991, and the deaths of the four men in Clonoe in 1992. In their desire to seek their justice the next of kin might wish to look closer to home.

Before continuing to look at the Clonoe ruling it might be of use to look at the role of the Inquest in the investigation process. It stands to reason that any death, whatever the cause requires a degree of investigation. If the death is suspicious then the investigation is usually conducted by the police or by the coroner or a combination of both. Where the death is attributed to “the State” then there is a requirement under both domestic and international law to carry out an “effective investigation”. What is effective has broadened in scope through various judicial rulings but in includes independence, thoroughness, impartiality and fairness. It should also be meaningful in that it leads or points to some conclusion such as prosecution (or decision not to prosecute), a change in practice or some form of restitution. Most commonly this includes deaths in prison, deaths caused by the police and in the Northern Ireland context, deaths caused by the security forces. In the early stages of the Troubles investigations were carried out by specialist investigators from the Royal Military Police. As civilian primacy returned investigations were conducted by Royal Ulster Constabulary. Following the investigation, a decision would be taken on any criminal charges arising out of the incident with the inquest being placed on hold until the conclusion of the criminal proceedings. Once completed the Inquest could take place.

The European Court of Human Rights in exercising its function under Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights – the Right to life – developed much of the case law concerning deaths attributable to “agents of the state”, with many of the cases arising directly or indirectly out of the Northern Ireland Troubles. The leading case of McCann & Other’s v UK arose out of the Gibraltar shootings in March 1988. While involving the deaths of three members of the IRA the applicable domestic law concerning investigation and Inquest were the laws of Gibraltar. The European Court was satisfied with the investigation, but found a violation of Article 2 in so far as it related to the control and planning of the operation. The principle established in McCann has been followed in numerous other court rulings.

In so far as Northern Ireland is concerned the next most relevant cases to come before the court were those of Jordan, Shanaghan, McKerr and Kelly v UK in 2001. The court held that in all those cases there was a violation of Article 2 as the investigative process was deemed to be inadequate. In particular it was held that there was a lack of independence in those investigating the incidents; there was a lack of scrutiny of the decision to prosecute ( or not to prosecute); the alleged perpetrator(s) could not be compelled to give evidence at an Inquest; the inquest procedures did not permit any verdict or finding which could play a part in any future proceedings.

Of note, in all the cases, referred to above, the European Court did not consider the actions of those individuals responsible for the deaths but concentrated on the conduct of the operation itself and the processes thereafter to conduct a prompt, thorough, impartial and fair investigation.

As a result, there has been considerable delay in Northern Ireland in conducting inquests and hence the recent Clonoe Inquest concluding in February 2025 but arising out of an incident in 1992.

With this framework established by the European Court the Coroner for Northern Ireland in making his determination exercised his function correctly. That is not to say that all will agree with his findings. Many, those with a service background or not, may fundamentally disagree with his conclusions over the perceived level of threat, the appropriate response to that threat and the level of force used. He adopts a clinical approach, attempting to analyse each shot fired rather than understanding the difficulties of engaging multiple armed targets at night in a complex, dangerous and demanding situation. He seems to rely heavily on the number of rounds fired in the incident, in this case over five hundred. He addresses in detail the wounds on each of the deceased but this he is required to do in order to determine the cause of death. The inference that might be argued is that five hundred rounds for four men is overkill and therefore excessive.

The key element of the soldier’s defence was the right to self defence and to use lethal force in these circumstances in the belief that their lives were in danger. The soldiers were aware that they were dealing with a seasoned IRA team who had just attacked a RUC police station with a heavy machine gun and small arms. In all likelihood it was reasonable to assume that each of the IRA men were armed and they were likely to open fire if challenged. To many this may seem to be a perfectly reasonable assumption.

The findings of the Coroner will now almost certainly involve further consideration of potential criminal proceedings against those servicemen involved.

Before rushing to the conclusion that the Coroner was acting in a vacuum devoid of any practical reality to conflict, war and the realities of military action he also was the Coroner in the inquest into the deaths of the three IRA members in the Coagh incident in 1991. In that case he found that the undercover soldiers were justified in their use of lethal force.

The reaction by the media and those representing the next of kin to the findings in the Coagh incident was comparatively low key, despite some revelations that might be considered to be of interest. Video surveillance of the incident ‘went missing’, the Coroner described the investigation as “woefully inadequate” evidence at the scene was “wantonly disregarded” and no questions were asked of those (in the military and RUC) who had planned the ambush. The referral to the DPP for the consideration of a prosecution he described as being based on the untested and unchallenged accounts of the soldiers. He gave himself and the Inquest system great credit for uncovering facts about the events in Coagh in June 1991. The causes of the deaths were gunshot wounds to the head and heart (McNally), to the head (Doris) and to the chest (Ryan). For some reason again reliance seems to be placed on the number of rounds fired – in this case over one hundred and fifty.

The Coroner in the Clonoe Inquest was not alone in his views. In October 2011 one of the getaway drivers waiting for the return of the gunmen in the St Patricks’s Church car park was awarded £75,000 in compensation for injuries he received. The judge in that civil case held that the evidence given by soldier A was “utterly implausible” and an “incredible” account. McKeever’s initial claim that he was in the churchyard at 22.30hs visiting a relatives grave might seem equally implausible. Strangely the sentence awarded to McKeever for assisting offenders (i.e. 4 men who were prepared to shoot into a police station with a large calibre machine gun) was a three year suspended jail sentence. Coney and Woods received identical sentences. It is not clear if the MOD settled the case for compensation.

The British Army unit involved has not been formally identified but is referred to as an “undercover unit”. At the Inquest the unit was simply referred to as a Specialist Military Unit. There is speculation that the unit is the Special Air Services Regiment and this is indeed very likely to be the case or at least a unit or members of UK Special Forces. UK Special Forces and its members attract considerable media interest including allegations of impropriety arising out of operations in Northern Ireland, Iraq, Afghanistan and more recently Syria. The interest may well be fuelled by Channel 4’s “Who dares Wins” or the BBC hit drama “Rogue Heroes” with the title itself conjuring up a perception of brave, fearless and utterly ruthless gung-ho mavericks. Coincidentally one of the heroes was a Northern Irish lawyer, Paddy Mayne.

The Army are not alone. The Metropolitan police face similar investigations and inquiries most recently into the shooting of Chris Kaba in London in Sep 2022. A police officer, Martyn Blake was prosecuted on a charge of murder and acquitted. As with the relatives of the Clonoe shooting, the family of Chris Kaba were not pleased with one campaigner stating that the outcome “reinforces the harsh reality that police can kill with impunity”. Sir Mark Rowley criticised the systems used to hold police officers who take lethal shots to account. Welcome to the life of the military Sir Mark.

For the servicemen who opened fire on the evening of February 1992 the ordeal is not over. The Coroner chose to refer to a MOD report at the time stating that the incident was – “an excellent security forces success”. From a military perspective it was a text book military ambush. The Clonoe incident coupled with the Coalisland and Loughgall incidents seriously weakened the ability of the East Tyrone Brigade to conduct future operations on the same scale and for this reason alone, might be considered a success and in some moral and ethical camps, justifiable.

Many people might quite rightly believe that the soldiers were operating in a “legal grey zone” in the most extreme and dangerous of scenarios. The fast-moving situation meant that the soldiers were forced to make split-second life-and-death decisions in real-time, which 33-years ago were regarded as reasonable and any doubt would be exercised in favour of the servicemen. But today those same actions are now being judged in a different legal and political climate, where the application of the law is black and white.

If it is accepted, for the sake of argument, that from a legal point of view the Coroner’s findings were “sound”, and that from a military point of view the Clonoe incident was a well-executed military operation is there any middle ground? Reassurance, although slim, might be drawn from two areas. – Firstly the remarks of Sir Brian Leveson referred to above. These words were said in the context of civil proceedings in a case involving the death of Azelle Rodney who was shot by police in 2005. Following an Inquest and then a Public Inquiry, the firearms officer, PC Anthony Long, was eventually charged with murder and in July 2015, acquitted. However, despite Leveson and many others echoing his words, they are rarely followed. Any lawyer responsible for making decisions in cases such should heed those words and where appropriate apply them. The second area where reassurance might be drawn is from the public. Not from the public at large but from the jury system which tries these cases. The lawyers in the Martyn Blake case must have agonised for months before deciding that it was in the public interest to prosecute AND there was a reasonable prospect of conviction. The jury took just three hours to unanimously apply common sense and disagree.

The Northern Ireland (Legacy and Reconciliation) Act 2023 attempted to draw a line in the sand over the court cases arising out of the Troubles which included civil claims and Inquests by the creation of a Commission to take over responsibility of all cases. The Act was immediately challenged in the Northern Ireland Court of Appeal who ruled the Commission lacked independence. The Act is now subject to a Remedial Order issued by the new Labour Government to resolve issues of incompatibility between the Legacy Act and the Human Rights Act – of which there are many. The Legacy Act, while popular in some camps, was flawed and would have been at odds with both Domestic and European legislation. The proposed conditional amnesty or immunity from prosecution for any person, terrorist or member of the security forces, was short lived.

The law may well be considered to be “an ass”. It seems counterintuitive to think that the men who plan an operation to steal a vehicle, mount a heavy calibre machine gun to it and blast indiscriminately into the compound of a police station with the intention of killing or wounding those inside, and to cheer loudly on the way to their rendezvous in the grounds of a church have the ability to fight for “justice” through their next of kin. The true heroes – rogue or otherwise – on the other hand have a longer and more arduous fight for justice. The Downing Street statement that “addressing the issues of the past must be done in a way that commands the support of families, survivors and importantly, the families of those killed serving the state”. Realising the obvious omission of a reference to the heroes, a spokesman added “any veteran who served during the Troubles is provided legal support, where appropriate”. Soldiers, unlike the police have no Union but rely on the help and support of those they know they can trust – their colleagues. This last statement by the spokesman must be of very, very cold comfort.

Phil McEvoy OBE was an Army lawyer. He served in Northern Ireland during the 1980’s and 1990’s and was one of the so called “Flying Lawyers” who were dispatched in the immediate aftermath of shooting incidents to represent soldiers during police investigations. He represented soldiers in some of the incidents referred to in this article. He did not represent any of the soldiers in the Clone incident. Phil served as Head of Operational Law from 2005 2009 Deputy Head Service Prosecutions 2009 – 2014. He retired from the Army in 2014 in the rank of Brigadier.