EXCLUSIVE: NSN speaks with Eric Patterson on the Just War Tradition & Quest for Peace

Today, NSN had the privilege of discussing ‘just war’ with Eric Patterson, President of the Religious Freedom Institute in Washington, DC.

Patterson is an expert in two areas: the ethics of war and peace, and religious freedom policy. He has long advocated for better training for government officials on how to understand the religious dynamics of international contexts and the links between democracy and religious freedom.

Patterson’s government service includes time at the US State Department, service as a White House Fellow, and over 20 years as an Air National Guard commander. He is the author or editor of 22 books, including Just American Wars, Politics in a Religious World, and Ending Wars Well.

NSN: Could you provide us with a brief overview of your latest book, “A Basic Guide to the Just War Tradition” – Why do you think it’s important for people to have an understanding of the Just War Tradition?

Eric Patterson: This book is an introduction to the just war tradition, which is the basis for today’s law of armed conflict and international law. The just war tradition is a part of Western civilisation that dates back to the Greco-Roman, Jewish, and early Christian eras, with fundamental questions about government, citizens, and self-defence. When is it just to employ force? How can force be employed justly when the decision has been made? How do we work towards the ultimate goal of peace? This book is really about those three questions, but it’s distinctive in the fact that it tries to provide answers tied to some of the media and fiction of our day, to make it an accessible resource on these issues to military personnel, chaplains, pastors, students, and concerned citizens.

Secondly, it’s tied to some of the fundamental values that most of us have in the UK and US. We believe that governments should operate on principles of stewardship. We want our decisions to be common good decisions made on love of neighbour, and this book talks about the difference between hatred and righteous indignation, between an unjust peace and a righteous peace.

NSN: How can we measure whether authorities are acting with the right intent instead of motivated by hatred, revenge or radical ideologies?

Eric Patterson: The just war tradition really starts with the question about when it is moral to go to war, and that starts with legitimate public authorities, in other words, governments, deciding on a just cause with right intentions. So, when we’re talking about force, whether it’s law enforcement or the military, it’s government authorities who make that decision based on the protection and the defence of their own people, allies, or neighbours. And, that just cause, as Augustine told us, includes things like righting past wrongs, preventing future wrongdoing, or punishing wrongdoers, and so clearly, there’s a self-defence and a justice set of categories there for making these decisions. One of those things that’s very important in the Christian tradition is what motivates us, what are our intentions? In other words, are we being motivated out of love of neighbour, out of wanting to protect and defend? Is our goal the common good? You can see, there’s a difference between righteous indignation focused on justice, i.e. righting a wrong, versus wrathful hatred that just wants to destroy. Those key elements of making this decision.

NSN: In your book, you also talk about last resort and proportionality. How does one determine if a government has made reasonable effort in diplomacy?

Eric Patterson: As we talk about these things like proportionality of ends and likelihood of success, I want to recognise that it’s very hard for political leaders, if they have been attacked unexpectedly.

Think, for instance, about the United States at Pearl Harbour on December 7th, 1941. Leaders were operating without the sophistications of computers and technologies, trying to make decisions with imperfect information and limited communications. I think about Israel on October 7th of this year. Although they knew that they were vulnerable to attacks, no one expected, or very few expected the type of attack that happened, and then they’re responding in real time, so the principles that you mentioned are secondary, important, prudential decisions that leaders make, often after events are already escalating.

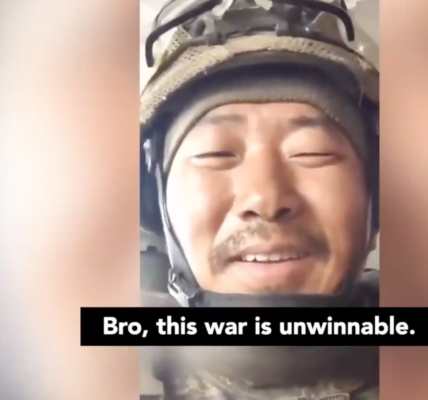

First, what is the proportionality of going to war, using force to our end, to our objective? It’s important to think not just as a victim (e.g. “we were attacked), but what was the nature of the threat to us when we prepare to respond with force. Tied to that is this idea of likelihood of success and counting the cost of our goals. What are our ends in this? And what are intermediate types of success? Think about the Ukrainians attacked by Russia, no one thought that they could win, yet they continue to fight a valiant effort almost two years on. One of the successes of the valiant defence of the Ukrainian military and the Ukrainian people was that eight-million civilians got out of the way of the Russian army as the Ukrainian defence forces moved into position, and that’s a success.

Last resort means that you’ve taken every reasonable effort, maybe in using economic sanctions, diplomacy, working with allies to try to avert bloodshed, but that’s only a reasonable principle. There’s no thought that one has to be at a position where you’re being decimated before you can use force.

NSN: Take the Russia-Ukraine war, for example, the Russians have not acted with restraint, so how do we defend against that, and what is Ukraine’s probability of success?

Eric Patterson: It’s clear that the Russians have not acted with restraint. They have attacked civilians; illegitimate private and public targets including libraries, hospitals, and churches were attacked, so, they have violated principles, such as discrimination, which means making a distinction between a legitimate military target and a private or civilian person or target.

What can be done? Well, what it doesn’t mean is that the defending party should act in kind. In other words, just because Russia attacks civilians doesn’t mean that Ukraine should try to bomb Russian cities. Frankly, I think that there’s probably a lot of people in Ukraine who have wanted to take the fight to the Russian citizenry, but they haven’t and so, a large part of the attacks, even outside of Ukraine’s borders have been on strategic targets, like Navy ships or energy supply depots or armament depots.

NSN: What will happen when US defence aid dries up? What do you think the outcome of the UKR-RUSS war will be?

Eric Patterson: Well, we’re doing this interview just a few days before Christmas 2023. There has been a stall in the U.S. Congress on providing more aid to Ukraine due to the ridiculously awful situation on the U.S. southern border, which is a security threat of great proportions here.

Ukraine does need this defence aid and it is perfectly legitimate for outside governments to provide the military armaments to allow a country to defend itself. Some people have said, is there something unjust in giving weapons to Ukraine? The answer is absolutely not.

The Ukrainians are in a self-defensive posture fighting to reclaim their own territory, and so it is perfectly ‘just’ for them to be fighting against Russian mercenaries and soldiers who are on their home soil of Ukraine. That said, I think that there’s a lot of hope in the West that not just the United States, but the Western alliance will ramp up the production of armaments at home and continue to send the vitally needed military supplies to Ukraine.

NSN: In your book, you argue that whenever we “dehumanise the enemy”, the war will devolve away from Justice, can you explain what you mean by this?

Eric Patterson: One of the most horrific parts of war is when the two sides dehumanise the other and no longer see them as human beings but see them as fiends or animals.

I think in the Israel-Hamas war, on the Hamas side there’s a double evil there. One is the dehumanisation of Jews and a Jewish nation beyond claims of political illegitimate, labelling the Jewsas evil and subhuman.

A second evil is the culture of death that Hamas raises its own young people, particularly it’s young men in, which is a form of dehumanisation if you think that they raise people in a culture of death that glorifies martyrdom and that involves killing other nation’s civilians. It really is a double evil in that sense. When it comes to Israel, I do think they’re perfectly just to be prosecuting this war. I do think a question for leaders that’s a very difficult one is how do you not pass on bitter generational hatred to your grandchildren and great grandchildren?

And that’s one of the beauties of the just war tradition. The focus on training troops, emphasising restraint, and recognising common humanity among all individuals, even those considered bitter enemies, leaves a path that perhaps a former adversary at some point, might be able to coexist in the same world as us.

NSN: Why do you think Western governments have not been able to stop radical Islamist ideology from spreading? How do we stop hatred flowing through the generations as we are seeing playout in the Hamas – Israel war?

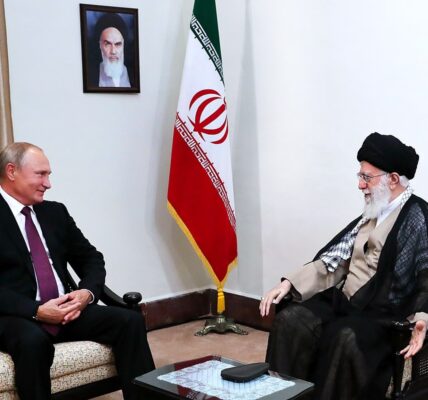

Eric Patterson: One source of violent Islamism that we are seeing lies in authoritarian leaders in the Muslim-majority world who radicalise their own youth through heavy-handed, harsh treatment. Some of the most radical terrorists often come from highly religious states like Saudi Arabia where young men have seen the governing class as corrupt and have been enticed by messages that seek a pure Islam and fight the internal and external jihad.

Instances of such radicalisation can be observed in groups like al Qaeda, so-called Islamic State, and Boko Haram. Dissatisfactionthat many, particularly in the Arab world, feel about their own structure of societies that are led by Muslim leaders is a significant catalyst, accompanied by the influence of radical clerics shaping a worldview inspired by early 20th-century communism. This narrative portrays an oppressor-oppressed dynamic, and that framework has become indelibly embedded in the types of messages that Osama bin Laden and others have given to their people over a long period of time.

Unfortunately, in the United States in particular, addressing the religious dimension of violent Islamism is often avoided, with alternative explanations given such as attributing violence to climate change rather than recognising that there is a violent Islamism perpetrated by these radicals that has certain intellectual and theological roots. Countering those ideologies where they occur around the world is crucial.

NSN: How would you, in teaching the just war tradition and theory, conduct statecraft in a way that perceives peace with justice when dealing with enemies such as Hamas or Russia?

Eric Patterson: One of the great threats, as you know, in Africa is Boko Haram and so-called Islamic States-West Africa Province, that are very destabilising to Nigeria.

Nigeria is a country that’s a top five oil producer, and a strategic anchor in West Africa. It’s critical for global petroleum reserves, and it’s a country of well over 200 million people. It dwarfs its neighbours. In the past, it’s been an important security linchpin for ECOWAS for West Africa. Bizarrely, the United States ambassador to Nigeria says that the reason that about 4,000 Christians are killed a year by Muslim insurgents and criminals, and the reason that about a total of 10-12,000 Nigerians are killed at the hands of terrorists over the past 15 years, including manyMuslims, is climate change, and not the violent ideology of Boko Haram, not the violent ideology of ISIS, or the radicalisation of youth.

A just war statecraft perspective would say, how do we help the Muslims and the Christians and everybody in Nigeria achieve peace and security against violent groups, whether they’re criminal mafia, criminal gangs, pirates, brigands, or Islamic terrorists? And then you work with people across those lines to buttress government institutions and go after the bad guys.

In the Nigerian case, imagine the same coalition that defeated ISIS, bringing in Arab countries who hated ISIS, and al-Qaeda, governments like Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and others, and having them partner with the US and UK and the government in Nigeria to crush the bad guys. That is not the approach that’s been taken, but that’s the type of way where you show it’s not a religious or ideological war waged from the West against Nigeria or against Muslims: we’re bringing allies together to get to the root of the problem.

NSN: Do you think the UK and the US have acted thus far in accordance with the just war tradition? What could they be doing better? Do you think peaceful means are as effective as opposed to using force when sometimes we’re required to, when sanctions don’t work, when negotiations don’t work?

Eric Patterson: I think that deterrence is an important but often overlooked element that precoceeds from the just war idea of restraint. So much of what we’re talking about, authorities acting just causes with the right intention, limiting the destruction, if we were to encapsulate that we’d say what we’re talking about is a moral ethic about restraint.

The ways that deterrence worked in the Cold War, whether it’s nuclear deterrence, the overall policy of containment, buttressing allies, providing weapons so a country can defend itself rather than keeping it weak, helps keep the peace and avoid hot war. Unfortunately, our policy with Ukraine in recent years,until this war, was to not give them weapons lest it seemed provocative to the Russians. Instead, what happened was that Ukraine was in a situation of provocative weakness that invited aggression. Deterrence is a policy in accord with just war statecraft.

Alliances are a policy, like the NATO alliance, that are designed not to go to war but to provide collective security. Let me say one other thing about deterrence, I believe that the reason that Israel was so aggressive in prosecuting the war in north Gaza was because they were sending a message to Iran, and a message to Hezbollah – if you come in from the north, this is what’s going to happen to you, and so, in the context of hot war, I think Israel’s determined response was in part a message of deterrence to Hezbollah.

That doesn’t take away a level of responsibility from Israel to think in terms of its long-term neighbourhood and what the ramifications are for this. Israel’s been very careful about not targeting hospitals, if there’s a major Hamas command centre under a hospital, you might think that they’d bomb it. Look at what they did. They entered that hospital with force and evacuated the people from the hospital.

We have news reports now that widely cited that there was an entire wing of the hospital that was off limits to doctors and patients, that was above ground, that was used by Hamas regularly, plus the tunnels underneath. Thus, Israel is in an extraordinarily difficult position and every action that they take are ones that could endanger or kill their own citizens who are being held hostage as well as Gazans who are caught in this conflict. There’s really no easy answer to this. The leadership of Israel has to act on its long-term security interests.

NSN: Do you think that a two-state solution will ever be achieved?

Eric Patterson: When it comes to a two-state solution, recall that this was a UN widely supported decision after World War II to do a two-state solution in the region.

Sometimes we act as if the countries in the region, say, Jordan or Iraq, are ancient countries and Israel is somehow an interloper. That’s really not the case. Most of these countries that were old Ottoman provinces were created either immediately after World War I or in the early 1940s. And so, the promise that was made to the Jewish people in the Balfour Declaration of 1917, as well as promises that created Jordan and Iraq, to me, those all seem perfectly legitimate because many of these were people living on the ground. There was a large Jewish population in the region, and so the two-state solution of 1948 makes a lot of sense. This has never been accepted by some Arabs in the region, and particularly violent groups like Hamas have not accepted it. They had a chance to accept it in 1948, but went to war in 1948, 1956, 1967, and1973. In each case, there was some sort of aggression against Israel.

I think one point of hope, for the region is look at the Camp David Accords of 1979, when a former military general, Anwar Sadat, as Egypt’s president, and a very right-wing Israeli prime minister, were able to come together and create a cold peace that has endured for a full generation now.

And so there is hope of a two-state solution. You can’t have it with a Hamas ideology that calls for the extinction of the Jewish people, but you can have Jews and Arabs living side-by-side at least in a cold peace in the region.

Separate from that is the rise of anti-Semitism. My organisation is actually going to publish a

small study on that this week. It is absolutely true that there’s been a shocking rise in threats of violence and some attacks in the UK,in the United States, and elsewhere. Antisemitic incidents in the US rose by about 400% in slightly over two weeks since the Israel-Hamas war began.

At the heart of this, and many people over the age of 35 have been totally shocked to see young, white college students at universities in Canada, the US, and the UK, and other places marching in the streets saying hideous things that we never thought we’d ever hear again, such as ‘gas the Jews’, and other genocidal ethnic cleansing types of claims. There’s a twisted logic here that somehow the 9.3 million people living in Israel, it’s not 100 or 300 million, are colonial settlers that have somehow stolen a vast body of land from a tiny minority that is there.

Israel is a very small society. It’s a diverse society. It’s only 9 million people, many were Holocaust refugees who built something that is amazing and beautiful there. And frankly, I’d like to see that for the Arabs, the Palestinian population that’s there as well. I’d love to see them thriving rather than raising their children in this kind of culture of death, which is the basic textbook of Hamas.

NSN: Lastly, how would we put theological teaching about peace, love, and justice, which runs deep through Christian history into action? What do you hope the teachings of your book will achieve?

Eric Patterson: One of the beautiful things is that the Abrahamic traditions all have some of these basic principles, including Islam, about limitations in warfare, about recognising the common humanity, including people of other faith traditions.

Whether it’s the Muslim majority that Hamas supposedly represents or the Jewish majority in Israel who are largely actually secular and abide by the laws of armed conflict and deeply believe in them, or whether we’re talking about the Western Judeo-Christian heritage, there’s a huge intersection here on valuing human life, on acting with restraint, on recognising the distinction between legitimate military targets and others.

We want to establish an enduring, secure order, a basic political order, stop the bloodshed, stop the violence, when appropriate we want to work towards justice, and that’s usually very limited.

We usually don’t get the Nuremberg trials, but at times there are people to be held accountable, but with an eye towards conciliation.

How do we come to terms with the past in a way that we can see former adversaries as shared partners in the world in which we live?

Think about how World War II ended and Western Europe’s long-standing peace, including between Germany and France.

Was all of that possible in 1945 or 1946 or 1950? Of course not. It took evolving threats (e.g. from the Soviet Union), took the rebuilding of Europe, Marshall Plan aid, and other things, and it also took leaders who were willing to reach out their hands in acts of conciliation. I think the most important of those didn’t happen until 1970 when the Chancellor of West Germany went to Poland to a war memorial. Remember, the Germans attacked Poland. That’s what started World War II in 1939, yet he knelt at a war memorial, and people understood in 1972 that this was an act of conciliation.

It was an act in a sense of contrition, and that symbolic moment by a leader was a huge olive branch to the people of Poland, but it didn’t happen right away. Think about how long from 1945 to 1972, those minor steps in the Cold War that got to that point, but leaders have a role to play in doing this, and we look for statesmen like Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, the Duke of Wellington and Marlborough, and George Washington who, when there’s victory, look for the chances for there to be conciliation.

NSN: Finally, to wrap up, if there’s one thing from your book you’d like to share with our readers, what would it be?

Eric Patterson: I’d encourage people to reflect on the concepts of rightful love and rightful anger. Often, we ponder about loving our neighbours and turning the other cheek, but what does that truly look like?

As C.S. Lewis once said, when Jesus mentioned turning the other cheek, he was addressing everyday interactions among local villagers—encouraging humility and avoiding unnecessary conflicts. Lewis clarified that, of course, this didn’t mean stepping aside for a homicidal maniac attempting to harm a child.

This stark example underscores the idea that turning the other cheek or pursuing peace doesn’t negate the responsibility of those in government or leadership roles to protect and defend. It’s a form of rightful love, protecting society. Similarly, anger or righteous indignation, when rightly directed, is often intertwined with love.

Righteous indignation can stem from a love of country, a desire to protect neighbours, or a commitment to justice. It stands in stark contrast to vengeful wrath and hate. In the book, I draw a parallel between characters like Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader. Both experience anger, but Luke’s is motivated by love and righteous indignation, while Darth Vader’s is driven by fear, anger, and destructive hatred. Luke resists succumbing to the dark side, offering a valuable lesson for us all.

Recognising the distinction between a restrained but powerful use of force and a violent, hateful, and destructive approach is crucial. This distinction is evident in law enforcement, where we expect force to be applied with restraint, and in our military actions.