One Trident sub could ‘incinerate 40 Russian cities’: Why Putin should fear Britain’s nuclear arsenal

Royal Navy submarines have suffered a few mishaps recently, but the country’s Trident programme shows we’re still a potent threat

“I think they appreciate our capability. What is obviously important is that they appreciate that it is what it is, which is a credible capability,” the Prime Minister said on Wednesday during a visit to greet the return of HMS Vanguard, after what is believed to have been more than 200 days at sea.

But is he correct? Do Vladimir Putin and co actually quake at the thought of the UK’s arsenal being trained on Russian targets? After all, the Royal Navy submarines have suffered from a few embarrassing mishaps in recent years, including a number of missile launch failures and a collision with a French nuclear submarine during a secret mission in the middle of the Atlantic.

‘Continuous at-sea deterrence’

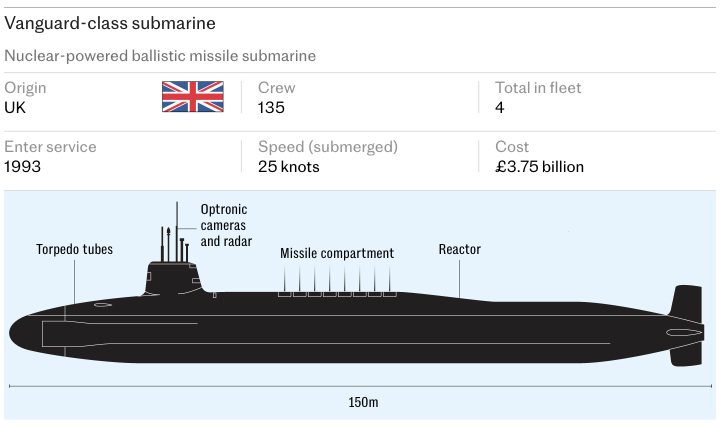

The Trident programme consists of four submarines HMS Vanguard, Victorious, Vigilant and Vengeance. The first boat, HMS Vanguard, was commissioned in 1993 and the last in 1999 – so they are all coming to or have already exceeded their 25-year lifespan.

Each submarine can carry up to 16 ballistic missiles, loaded with 12 independently targeted warheads a piece. In theory, this means a single vessel could potentially deliver 192 warheads in a single volley – although current UK policy limits the number of warheads permitted on board each of the submarines to 48 at a time.

One of these submarines must be at sea at all times. This is known as the “continuous at-sea deterrence”. It is the cornerstone of UK defence strategy and the ultimate guarantor of the nation’s security. Two other submarines are armed and should be ready to deploy at short notice while a fourth is usually undergoing some form of maintenance.

How close the Royal Navy has ever come to failing to meet this crucial requirement for any meaningful length of time is unknown – virtually everything to do with nuclear submarines is highly classified.

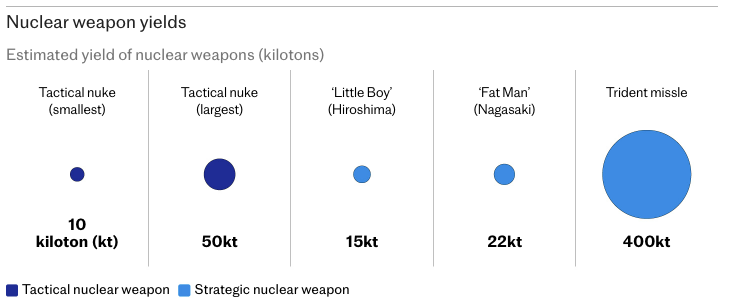

What is clear, however, is that Britain’s nuclear strategy is now solely dependent on Trident given that all tactical, lower yield nuclear weapons were decommissioned at the end of the Cold War. This dependency and Russia’s increasing nuclear belligerence has led to calls for Britain to rebuild its nuclear arsenal to allow it, if deemed necessary, to deploy tactical nuclear weapons and ultimately avoid having to use missiles capable of the destruction of cities.

Adding to the sense of anxiety, the Royal Navy’s trident submarines have suffered the ignominy of two relatively recent missile test failures. In January 2024 a test firing from HMS Vanguard failed. The missile failed to launch properly and crashed into the sea.

The Ministry of Defence described the incident as an “anomaly” and emphasised that the failure had “no implications for the reliability of the wider Trident missile systems and stockpiles”. Eight years earlier in 2016, a Trident missile test from HMS Vengeance also failed, with the missile veering off course and eventually self-destructing.

Also of concern is the age of the fleet. The oldest sub in the fleet, HMS Vanguard, first entered service in 1993 while the last boat to be commissioned, HMS Vengeance, did so in 1999. And all four vessels will be expected to continue to deploy on secret missions for at least another 10 years yet.

A potent threat

Despite the vessels’s age, Rear Admiral Chris Parry, who served in the Royal Navy for 37 years from 1972 to 2008, agrees completely with the Prime Minister’s view that despite their age, the Trident submarines really do worry the Russians.

“One Trident submarine has the ability to incinerate 40 Russian cities very quickly. That is a lot of food for thought for Putin and that should make any world leader fearful,” he tells The Telegraph.

Britain’s Trident nuclear missiles are manufactured in the US but are jointly maintained by the UK and US, with the Royal Navy relying on the US for parts and technical assistance and returning the missiles to the US for periodic refurbishing.

While in the past such dependence on the US was not an issue, recent events, with Trump suggesting that Nato can no longer rely on US support, may create problems for the future.

Still, for now, Britain’s threat endures. “Putin knows what Trident submarines can deliver and that is something he has to factor into all of his calculations when he is provoking the West,” says Rear-Adml Parry. “Russian air defence systems are not that great. Russia is also the largest country on earth – it is impossible to defend against a ballistic missile attack.”

Nuclear protocol

The decision to launch nuclear weapons can only be taken by the prime minister – or a designated survivor following a nuclear attack.

Two designated personnel must authenticate each stage of the firing process before missile firing. The control is not actually a “red button”, as widely popularised, but rather a trigger, modelled on the handgrip of a Colt “peacemaker” pistol.

Locked inside a safe on each of the submarines is a “letter of last resort” from the prime minister, containing instructions on what to do if all contact with the command system is lost following an overwhelming attack.

The precise contents of these letters are never disclosed and are destroyed, unopened, when the keys to No 10 change hands.

The missiles themselves, meanwhile, have a range of 6,500 nautical miles and each has a speed of around Mach 19 – more than 13,000 miles an hour. This means that depending on where the submarine is based at the time, a target inside Russia, such as the capital Moscow, could be destroyed within 30 minutes of the order being given.

“Just imagine how vulnerable we would feel in the UK if we had given up all of our nuclear weapons,” says Rear-Adml Parry. “There have been problems but it is important not to overplay these events. The missile firings, for example, were about testing the launch process – there was too much focus on the missiles failing. Yes they are old, but they are still very capable.”

‘Trident submarines are old’

But that view is not shared by everyone. There are growing concerns in some areas of the Royal Navy that the increasing age of Trident submarines means that they are an accident waiting to happen.

“Trident submarines are old and this is an obvious concern,” a senior naval source tells The Telegraph. “When something goes wrong on a submarine it has the potential to be catastrophic. Obviously the older something becomes, the more prone it is to some sort of failure that is why ships and submarines have a life span – you can’t constantly make do and mend, especially with a submarine.

“There is always risk associated with submarines but the older they become, the more vulnerable they become and the greater the exposure is to some sort of failure and the potential damage to national prestige obviously increases.”

Patrols by one of the UK’s nuclear-armed submarines – which used to last three months – have had to be extended in recent years because of prolonged periods of maintenance and repair work on the other boats.

The fleet is operating well beyond its original in-service life of 25 years because of delays in the building of four replacement vessels.

‘An insurance policy’

Trident is also increasingly expensive with running costs around six percent of the UK’s defence budget, which was around £3 billion for 2023-2024.

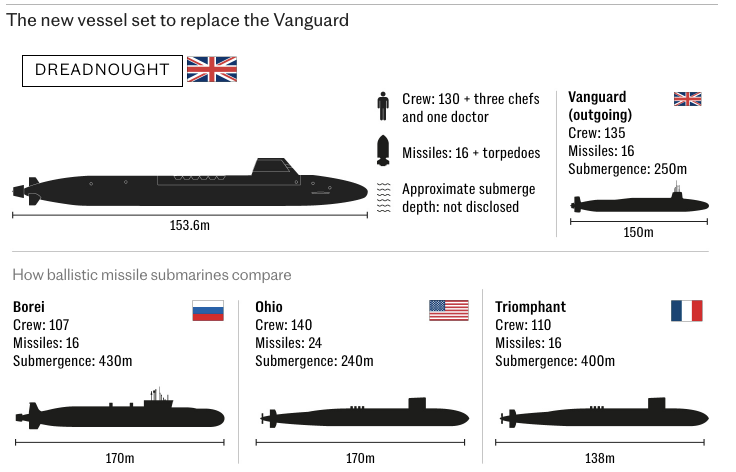

The current fleet will eventually be replaced by a new class of Dreadnought submarines – said to be as quiet as an idling car, allowing them to avoid detection.

HMS Dreadnought, HMS Valiant, HMS Warspite and HMS King George VI will at that point become the nation’s main nuclear deterrents. But that looks unlikely to happen for at least another 10 years and estimated costs are expected to be at least £31 billion.

Still, despite Trident’s soaring costs, the fleet’s age and the fact that it consists of just four boats, Rear-Adm Parry insists Britain’s nuclear deterrent packs enough of a punch to make Putin wary.

“This is one weapon system the British possess which will really worry the Russians,” he says. “And that after all is the point of a nuclear deterrent. It is an insurance policy – often expensive until you need it.”