South Africa is confronting an escalating kidnapping crisis, with 17,000 cases reported in just one year, marking a 260% increase over the past decade. According to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime (GI-TOC), this surge is largely driven by a rise in extortion. GI-TOC experts warn that extortion is rapidly spreading throughout the country and negatively impacting every sector of the economy. This criminal activity is often characterised by violence, murders, and mass shootings. In this article, republished with permission from the Vrye Weekblad in South Africa, Ali van Wyk speaks to the experts.

Let’s go for a ride: South Africa’s growing kidnapping plague

The first ingenious bank robber wasn’t the big problem when it came to battling crime. Nor was it the first major train or stagecoach robber. The same goes for the first car hijacker in South Africa or cash-in-transit robber. It was the copycats who became the issue. ALI VAN WYK talks to the experts.

IT’S A significant moment in the development of a nation when ordinary citizens become the target of organised crime. Even if it’s just a perception.

When trains are burned at Cape Town’s station, some of us can’t get to work, or people who work for us can’t reach us. We know we’re victims, but we also know we’re not the primary victims of the crime.

But when someone we know in our residential area is grabbed on the street, kidnapped, and ransom is demanded from the family, we know it could very possibly happen to us. Part of our fate is surrendered to a motivated, powerful and dark hand moving below the surface. That gang was coming for one of us – the kidnapped person wasn’t just hit by a stray bullet.

Not our problem

South Africans have long learned to live comfortably alongside the public operations of organised crime. Cape Town is a murder capital of the world, yet middle-class Gautengers move down to its suburbs in droves “because it’s safer”. Fact is, it is safer, because the Cape’s high murder rate is related to the Cape Flats gang wars. And they have been considerate enough to keep their “beef” out of the suburbs.

Kidnappings for ransom may have fascinated the ordinary person but didn’t make them feel unsafe. At one point, it was relatively common for wealthy Muslim businessmen in particular to be grabbed and for millions of rand in cash to be demanded for their release. Some of these detentions lasted for months, but the information that filtered through to the public was minimal and incomplete, usually because the victims’ families were too afraid to share information.

Some of these cases were sensational – on occasion one would read about the involvement of a notorious Mozambican syndicate. It appears that the arrest and conviction of the Mozambican and alleged transnational kidnapper, Esmael Malude Nangy, in Centurion early last year, left a large number of law enforcement officers and politicians very satisfied.

Some researchers and police members say that the entire technique of high-level kidnappings for ransom was imported from Mozambique, where there is an established culture of such kidnappings. These criminals focus almost exclusively on businessmen with a lot of cash on site, which was also the case with the wave of Portuguese butcher kidnappings in Gauteng.

A real wave or just a perception?

The picture on the ground has changed, however. A recent wave of kidnappings in Stellenbosch, the Eastern Cape, and Gauteng lets you sit up and take notice. In the Western Cape alone, 233 cases were reported to the police between April and June, and in nine of these cases, ransom was demanded, and in another five money was extorted in some other form.

A Stellenbosch student was recently kidnapped at 02:40 on a Thursday morning from Plein Street by two men in a vehicle and released a day later after her family paid a ransom. In June, a suspect was arrested in Caledon after the kidnapping of two students in the Franschhoek Pass. In two other incidents, two Stellenbosch students and a cyclist in Stellenbosch were kidnapped and in both cases transported to Grabouw, from where a ransom was demanded. An elderly British tourist was also kidnapped and released.

The suburbs anxiously watched for news about the kidnapping of Alize van der Merwe, a tourist in a rental vehicle, who was held for six days in September in the Eastern Cape, until she was released along with another foreign tourist, Xiaomei Tian.

The perception that ordinary people who appear to be upper middle class and reasonably wealthy have recently become targets of kidnapping for ransom has inevitably emerged, but one wonders if this is accurate, and whether it’s not a case of “white panic” – an unusually high number of cases involving certain population groups were reported in a short time. It’s simply a fact that kidnapping a white woman from Stellenbosch will receive a much higher media profile and put much more pressure on the police than the kidnapping of a black woman from Lusikisiki.

We indeed have a problem

Three seasoned crime experts all agree it’s not just white panic: “The number of kidnappings reported to the police has increased by 300% over the past decades. That’s dramatic. It increased by 10% just over the past year,” says Lizette Lancaster, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies. “While initially it was transnational syndicates demanding ransoms for kidnappings, increasingly it’s local groups doing it. It’s just local criminals who see that other people are making easy money from this.

“They might be less sophisticated, but they either target people about whom they have information, or people who simply look like they have money, and therefore it becomes more random. It’s happening more and more with people who are in the wrong place at the wrong time. The targets are people who run cash businesses and increasingly middle-class people who look like they have money.”

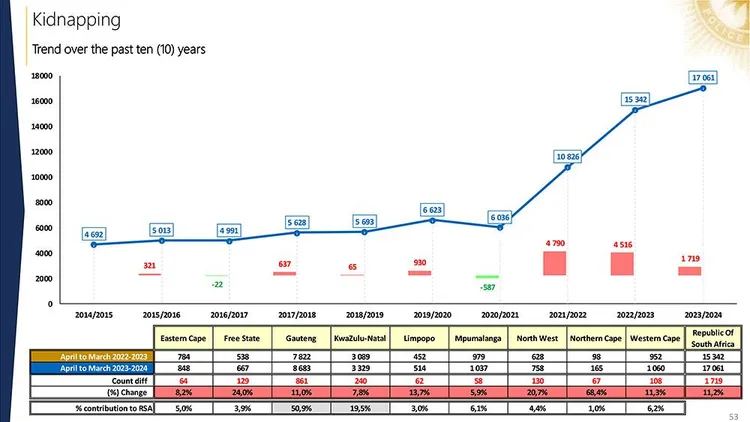

South Africa’s reported kidnapping statistics over the last decade. Note the dramatic increase in the last four years. © SAPS

Ian Cameron, DA member of parliament and chairman of the portfolio committee on police and a man with years of experience in crime activism, agrees: “I think it’s an extremely attractive business move for many of these criminals, because it’s low-risk in terms of them potentially being fatally wounded in … an attempt to rob a shop. They can get more or less the same amount of cash, because in many, many, many cases ransoms are paid.

“Also, importantly, the punishment, if you were to be caught, is extremely low. You can’t compare it with other crimes. It’s also easier to do than stealing copper cable. You’ll eventually make good cash, and the risk is low.”

Two types of syndicates are at work, the highly professional transnational syndicates, who only target the ultra-wealthy with lots of available cash, and the “local copycats”, says Jenni Irish-Qhobosheane, a researcher at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. “We see it even here in the townships with children being kidnapped, even though their parents don’t have much money.”

The baby of all mafias

Irish-Qhobosheane is one of South Africa’s leading experts on the massive extortion networks that have developed over the past 40 years, particularly in Cape Town and Gauteng. She writes about four major Cape Town networks in her reports – the oldest the protection and extortion network aimed at nightclubs and brothels, initially run by Cyril Beeka, but later by Mark Lifman and Jerome “Donkie” Booysen, and ultimately Nazif Modack.

Then there’s the extensive transport extortion, involving almost all taxi associations, who extort each other and other transporters who stand in their way, such as large bus networks, and nowadays long-distance bus networks. Irish-Qhobosheane says the taxi bosses will even go so far as to intimidate private individuals who offer lifts for people to work.

The third, newest type of extortion network, operating in Cape Town and Gauteng, is the construction mafia, which violently wedge their way into the industry through “local committees”, with the support of established local gangs. This mafia, which emerged in KwaZulu-Natal, enters a large construction site and demands that at least 30% of the contract work come to them. In some cases, they demand protection money – really illegal taxation.

In Gauteng, Irish-Qhobosheane also refers to the water mafia, which violently demands contracts and work for their members mainly from Rand Water, a multibillion-rand semi-state organisation that controls Gauteng’s water networks. This criminal network was responsible for the murder in a Johannesburg school hall of Teboho Joala, an executive of Rand Water.

The last extortion network Irish-Qhobosheane refers to are the local extortionists, the street gangs that initially demanded protection money from foreign spaza shop traders after the 2008 xenophobic attacks, in exchange for letting them live. They started with Somalis, and after Covid-19 began demanding protection money from local traders, then from all businesses in the townships and even ordinary private citizens.

Experts and the police are most worried about the growth in this aspect of crime in South Africa – the enormous increase in gangs dominating every aspect of township life. Irish-Qhobosheane frequently refers to Boko Haram (not related to the Nigerian Islamist movement) in Alexandra, as a classic example.

Extortion is our big nightmare

Besides the wave of gender-based violence and interpersonal violence, crime in South Africa might as well simply be called “extortion”.

Irish-Qhobosheane, like many other criminologists, constantly point to the connections among the networks, the fluidity of skills and personnel, and the involvement of old township gangs and prison gangs across a variety of industries. “Kidnapping is a little bit sophisticated in the sense that you need a house somewhere to hold the person, and grabbing the person is a bit of a risk, which is very similar to the risks in car hijackings and cash-in-transit robberies, but when it comes to other forms of extortion, like informal traders, it’s very often a case of the criminal going up against unarmed people. You have a weapon and you tell the trader to give you their money so they can trade in this area. It’s a low-risk activity.

“Look at the arrest of Bara (Yanga Nyalara) in Cape Town for example – he is one of the biggest alleged township extortionists, but is also linked to cash-in-transit robberies.”

This is the picture taking shape: A leader-criminal with a plan calls a meeting in a shebeen with a selected group of four or five criminals, one from a hijacking network, one from a cash-in-transit network, and maybe one or two soldiers from an ordinary township extortion network.

Let’s go for a ride

Another fact that all researchers emphasise is that many kidnappings are not planned kidnappings from the ransom tradition, but rather extended hijackings, or extended house or business robberies, and in many cases even hijackings or house robberies that go wrong and yield too little loot. Only 5% of kidnappings are indicated as kidnappings with ransom in mind.

By far most kidnappings are of the “let’s go for a ride” type, where the robber couldn’t get enough cash or jewellery at first contact, and now takes the victim in their car and drives around with them. The idea of a ransom is only cooked up during this phase.

Two or three hijackers hijack a professional in a BMW on a Friday night in Johannesburg. They drive around with a pistol to his neck, from ATM to ATM to withdraw all available money from his credit card, his checking account and his savings account. After he’s increased all his cards’ limits and cleared his overdraft facility, they have R120 000. That’s too little to divide among three people for a high-risk robbery and three hours’ work.

They take him to an apartment in Hillbrow, where they also force him to activate and withdraw from one or two loans which the banks had automatically preapproved. They now have R250 000. They realise their time is running out, it’s Saturday morning and his family is starting to look for him. With his sister and father, they do a flash version of what they had done to him, threatening them over the phone, and they walk away with R600 000 by Saturday evening. Not bad for a day’s work.

Was it a kidnapping? Technically, yes. Is it reported as a kidnapping? Sometimes. The question is really whether it’s reported at all. According to Irish-Qhobosheane, the police still have a lot of work to do to more accurately sort kidnapping statistics. There is a large overlap between kidnappings for ransom and extended robberies, hijackings, and kidnappings known as abductions, which are usually kidnappings within a family, for example, a father who kidnaps a child because he’s in a dispute over the payment of maintenance.

A large number of kidnappings for ransom are never reported to the police, out of fear of retaliation, and sometimes because people find it humiliating to have paid a large sum of money to criminals.

Are they coming for us?

So does this dark world directly target the middle classes, right into their neighbourhoods and streets, into their homes? The thought of a child being taken by invisible forces is unbearable for any parent. WhatsApp neighbourhood groups were the perfect breeding ground for a typical white-fear story about blonde little girls being grabbed by Nigerians (insert your own scary dark-skinned stranger here) in shopping centres like Tyger Valley or Cresta, and then being transported along dark smuggling routes into sexual slavery in Bangkok (or a similar scary-sounding place), where they are held and abused for 20 years and then discarded.

The fact of the matter is, as Lizette Lancaster says, even criminals don’t want to infinitely complicate their lives by kidnapping a middle-class South African child. This is the most well-looked-after class of people in the world, it stirs up tremendous emotion in a very resourceful community, it resonates in the media like few other crimes, and puts enormous pressure on the police and politicians to do something. It’s a very hot potato for a criminal.

Although human abduction and trafficking for sexual slavery are real and big problems across the world, young women are not recruited and trafficked from resource-rich communities to resource-poor communities, it is done the other way around. Children are taken in communities where the parents are so poor and disempowered that they can offer no resistance, and where the police are likely to be part of the syndicates.

The odds are much better of encountering victims of human trafficking from poor communities in Asia and Africa in a Cape Town brothel than encountering a middle-class South African victim of human trafficking in a brothel in Bangkok.

Be alert, but avoid panic

All three security experts believe, that while we shouldn’t become alarmist, it’s time for people to become aware that kidnappings are now more random, and one can be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Lancaster says: “In our residential areas, it’s still at a very low level, but be vigilant if you’re a businessman who is mobile and works with cash. Also, be aware of what’s happening near you. If Muslim businessmen or Portuguese butchers have recently been grabbed in your area, be alert!”

Ian Cameron says any middle-class person travelling in a remote area like the Eastern Cape, as happened with Alize van der Merwe, is necessarily at greater risk, because of the well-developed criminal networks in a province where management of the police is rather questionable. Cameron says the commanders of the kidnapping unit in the Eastern Cape are themselves under suspicion for various crimes.

However, Cameron is also surprised by the police response in the Alize van der Merwe case: “I was really impressed with the police and especially the Hawks in the Eastern Cape’s urgency to handle the case. They really went out of their way not just to do what they could, but to work with the private sector as well. It’s encouraging for me to see that the new [police] minister [Senzo Mchunu] feels so strongly about it and involves all stakeholders that he possibly can. This is something we haven’t had in the past.”

Irish-Qhobosheane also believes progress has been made nationally by the police: “There have already been many significant arrests around the larger networks. Several key criminals in the kidnapping networks have already been taken into custody.”

Still, Cameron is afraid that arrests, and even convictions, won’t reduce the momentum: “I think there’s significant involvement in all these structures from prisons, and that makes it complex, because many of the activities are co-ordinated, or approved, or instructions are given from correctional centres, and the minister of correctional services [Pieter Groenewald] indicated again today that they are well aware of this, and that he and the minister of police are looking at what they can put in place to stop it.”

And while there is good co-operation in places, the police, the National Prosecutions Authority, and correctional services are still far too fractured to be effective: “There’s a big problem that there isn’t an integrated effort between the police, jointly with the Hawks, the NPA, and even correctional services, but that piece [of the puzzle] between the police and the NPA, to purposefully remove certain key persons from circulation, so that you can put an end to the trend, in my opinion … it doesn’t exist.”

♦ VWB ♦