This week South Africans witnessed a moment of reconciliation that they thought had vanished at the end of the Mandela era – a Government of National Unity (GNU) was agreed upon. It is a power-sharing agreement between the African National Congress (ANC) and the main opposition party in the country, the Democratic Alliance (DA), with smaller parties, the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), and the Patriotic Alliance also agreeing to be part of the GNU.

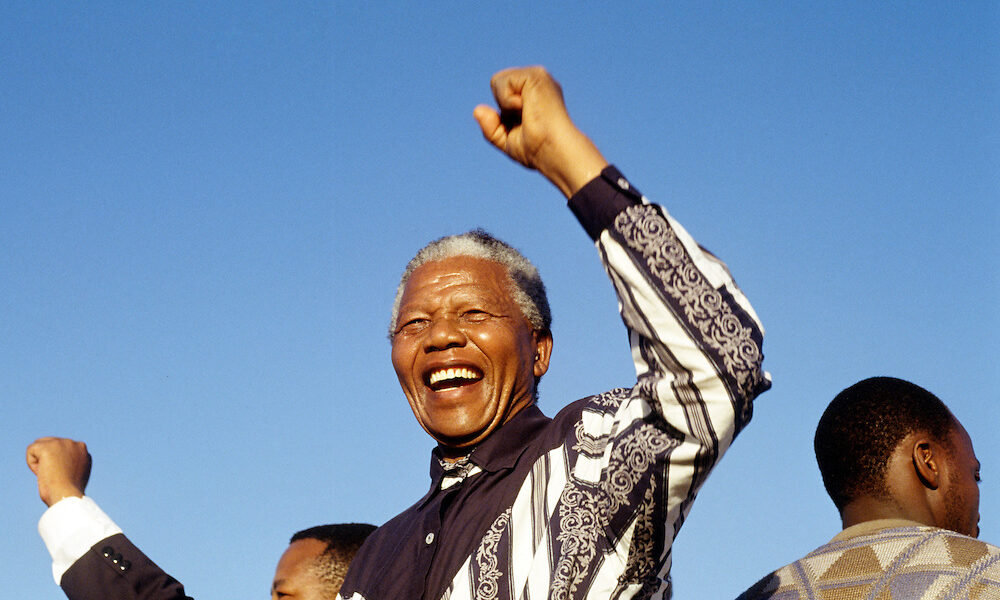

What makes the agreement so remarkable is not only that it was signed in Parliament in Cape Town as the first sitting after the country’s May election had already begun – it signifies a shift towards the middle ground in a world where many countries are veering to the right. It is also remarkable that the ANC, having lost its majority, accepted the results of the election, paving the way for the kind of reconciliation that Mandela aspired to.

A visibly exhausted South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, after being re-elected in a marathon Parliament session, called the deal a “new birth of a new era for our country” and urged parties to “overcome their differences and work together.”

“I will serve all and work even with those who did not support me,” Ramaphosa said.

DA leader John Steenhuisen declared that the era of finger-pointing was over. It was a time for democratic consolidation and new politics of cooperation, he said. “With the DA at the heart of a new multiparty government,” he said, “South Africa is ready to write a hopeful new chapter that defies the odds once again.”

However, not everyone welcomed the agreement. Julius Malema, leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), which some ANC leaders saw as a more natural partner, told Parliament that the GNU deal was a betrayal of many South Africans, accusing the ANC and DA of consolidating economic power under a white monopoly. He vowed to hold both parties accountable.

The EFF is part of a group that calls itself the Progressive Caucus, which holds 13% of the National Assembly and includes smaller parties, Al Jama-Ah, the UDM, UAT, ATM, and the PAC, with a combined 48 of 400 seats in the National Assembly. This group accused the ANC of sidelining them from the GNU talks and warned of consequences if the ANC formed what they called a grand coalition with the DA.

The road ahead for the GNU in South Africa could be bumpy. Maintaining cohesion between the ANC, plagued by accusations of corruption and failing infrastructure, and the DA, which had up to now been a vocal opposition party and had often challenged ANC decisions in court, will not be easy.

Constitutional expert Prof. Pierre de Vos noted the most surprising aspect of the agreement is that cabinet positions require mutual consent from both the ANC and the DA. This, he wrote on Twitter (X), “makes it impossible for the DA or ANC to push through policies against the will of the other party.”

Although cabinet positions are yet to be finalised, a source close to the negotiations indicated that the DA could occupy between five and nine executive positions. Deputy President Paul Mashatile will likely retain his position, and a second Deputy President role may be created for IFP leader Velenkosini Hlabisa, which would require a constitutional amendment.

Political analyst Prof. Theo Venter warned that the biggest threat to the new political dispensation could come from KwaZulu-Natal, where Jacob Zuma’s uMkonto we Sizwe Party (MK Party) is the largest party in the province.

Zuma tried to prevent the country’s Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) from announcing the election results, claiming the election had been rigged, and he subsequently attempted to prevent the first sitting of the 7th Parliament by means of a court application. The MK Party and its supporters also spread disinformation online in a campaign reminiscent of the tactics before the July 2021 unrest.

After failing to prevent the Parliamentary sitting, the MK Party boycotted the opening ceremony, and Zuma indicated that he would not be sending his 58 Members of the National Assembly to Cape Town. However, he did a U-turn and announced that his elected members would attend provincial legislatures to be sworn in as Members of the Provincial Legislature. The MK Party was, however, blocked from ruling the province when the IFP, ANC, DA, and a smaller party, the NFP, united to form a multi-party provincial coalition government.

A political analyst told NSN that although Zuma and the MK Party may not attempt an open insurrection to destabilise the GNU, he expects Zuma and the EFF to exploit every division in society to hinder the economic growth that the country desperately needs.

Despite doubts about whether the GNU will hold and threats from Zuma, the MK Party, and other opposing political groups, there is a new sense of optimism among South African citizens living with power blackouts, deteriorating services and an ailing economy, that the backward slide that began under Jacob Zuma’s reign, could be reversed.

This optimism was also reflected in financial markets as stocks rallied and the rand gained in value as investors cheered an agreement between rival parties to back the re-election of Cyril Ramaphosa. The Economist described it as “a remarkable new era – a national unity government can save democracy and the economy,” the paper stated.

At a news conference, ANC Secretary-General, Fikile Mbalula remarked that South Africa was maturing. “Nelson Mandela was shining on us yesterday,” he said.

Many South Africans on social media echoed this sentiment, hoping that their country will again become Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s Rainbow Nation.