South Africa’s Election: Pivotal for Geopolitical Alignment – Dr Frans Cronje

South Africans are voting this week in national and provincial elections, and polls indicate that support for the ruling African National Congress (ANC) could fall below 50% for the first time since 1994 when the country became a democracy. This erosion of support signals a new era of coalition politics for South Africa. In an interview with National Security News, Dr Frans Cronje Chair of the Social Research Foundation in South Africa highlighted that the ANC’s choice of coalition partner could not only alter South Africa’s path but also have wider regional and geopolitical implications due to the country’s strategic location along key maritime routes and its influence in African politics. He said it was “quite unclear’ whether the ANC would, if it loses substantial support, align itself to political parties like the Democratic Alliance with a more Western focus, or choose left-wing political allies like the Economic Freedom Fighters of MK Party which would shift it allegiance towards the Russian/China axis.

The Social Research Foundation’s poll tracker modeled on a 60% turnout, indicated that the ANC national support stood at 43% on 27 May.

Key edited quotes:

Ruling party support is being eroded by Jacob Zuma’s MK Party

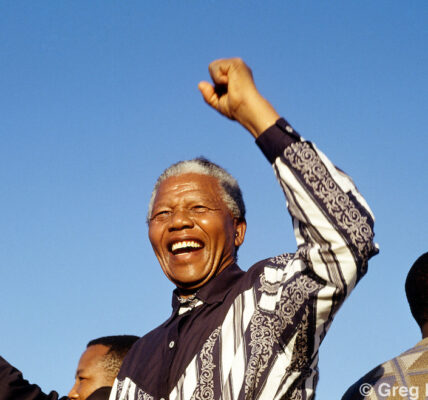

South Africa transitioned to democracy thirty years ago, ending the apartheid era. Nelson Mandela led his party, the African National Congress (ANC), to victory in the first democratic election in ’94, securing about 63 percent of the vote.

In its first decade in power, the ANC saw its support increase, peaking at about 70 percent in 2004. This dominance was a result of success. The number of employed people doubled in the ANC’s first decade in power, and there was extensive state-driven welfare and service delivery. This included housing and electricity rollout programs. The percentage of families without electricity fell from just under 50 percent at the end of apartheid to under 20 percent at the end of the first decade of democracy. Ten formal houses were built for every new shack erected in that first decade, and ANC support increased as a result.

However, many of these trends reversed in the second half of the democratic era. The country’s strong economic performance in its first 15 years as a democracy slowed as it ran out of electricity. Large scale blackouts affected industry and households, often for hours a day. Corruption became much more prevalent, and investor sentiment on South Africa plummeted. Levels of fixed investment as a share of GDP dived steeply. The job creation of the first decade slowed down, and the improvement in living standards stagnated and then began to reverse.

As a result, support for the ANC began to wane. In 2019, when South Africans last voted for a national government, support fell to just under 60 percent. For the first time, it was just under 58 percent. In fact, polls through 2022 and 2023 put support at around the 50 percent mark.

That remained the case until earlier this year when a new startup party, the umKhonto weSizwe (MK Party) on the East Coast, led by a great rival of the current president and a former leader of the ANC, launched. In the politically significant province of KwaZulu Natal, that party quickly gained about 10 percent of the vote. As a result, the ANC, which had been polling near 50 percent, started polling near 40 percent. They have, however, staged a bit of a fight back over the past several weeks.

We run a track, measuring these things every day of the week. Currently, the ANC is sitting in the mid-forties but is tracking a bit upwards. With two to three days to go until the vote, if you follow the track, it looks like the ANC may surrender its national majority for the first time.

For the first time since becoming a democracy, South Africa may be in a position to see some kind of change in administration.

Where will the ANC in a new coalition align itself after the election?

If you’re observing South Africa from abroad, this is the crucial question. It’s not just a question that will be answered in the coming weeks or months as a potential new administration is formed. It’s a question that will be asked of South Africa over the next decade, as it seems likely, based on current trends, that the African National Congress’s diminishing support will accelerate.

The first thing I’d say to anyone who asked that question is, remember that when South Africa became a democracy in 1994, it was in a unipolar world. The Cold War had ended, the Soviet Union had collapsed. Much of the Western world was beginning to live in what it thought was the era of the end of history, that the last great threat to the Western liberal democratic order had collapsed.

Liberal democracy had triumphed in the world and was expected to spread throughout the world. For the African National Congress in South Africa, which had long been housed in exile in the Soviet Union and East Germany, it needed to tread carefully, because its great Soviet ally had faltered. China was clearly emerging, but had yet to firmly establish itself as a global power.

The ANC’s relationship with key Western rivals have blossomed, future alignment unclear

The South African government maintained relatively strong relations with Western capitals. There were contradictions in those relations. However, over the years, as Western democracies, particularly in Africa but also elsewhere, have been reluctant to bring hard power forward, have perhaps to some extent been on the retreat, and as a multipolar world has emerged, South Africa’s governing administration has found that it doesn’t need to be quite as circumspect as it once was.

Relationships with key Western rivals, China, Iran, Russia, have blossomed. The inflection point of this change of administration feeds exactly into that point. What happens now? Will an administration or coalition government be delivered that aligns more firmly with the West? Or does the alternative happen? Is a coalition government starting to emerge, possibly already doing so, that aligns South Africa far more

In South Africa, the official opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, aligns broadly with Western thinking. It’s a typical Western liberal democratic organization. If the faltering African National Congress (ANC) leadership finds itself needing a significant partner, the Democratic Alliance, which is expected to secure between 20 and 25 percent of the vote in this election, could be a potential ally. If the internal factional fighting within the ANC leans West, forming a coalition with the Democratic Alliance would be an obvious choice. The result would position South Africa more as a Western ally.

However, alternative options exist. The MK party, led by Mr. Zuma, a former leader of the ANC and a significant rival of Mr. Ramaphosa, the current president of South Africa and leader of the ANC, would likely seek to ally against the West. This party is polling at around 10%. There’s also a second relatively far-left party, the Economic Freedom Fighters, a splinter group that emerged from the ANC over a decade ago. They have explicitly stated that they would align South Africa firmly against the West, even to the extent of arming Russia in its campaigns in Ukraine.

It is completely unclear at this time which direction the later alignment will take. If the ANC’s support is currently in the mid-40s, it will likely cobble together a government with small ‘rats and mice’ parties, the one percenters, two percenters, just to get over the line. It will then delay any firm decision on whether to align pro-Western or anti-Western.

However, in due course, we vote every five years on a national level in South Africa. That question will be answered. It is quite unclear when that decision will be made. Will it be a shift to the West? Or will it be a shift against the West?

There are implications not just for South Africa, but also for observers around the world, and they are really very significant.

G20 chairmanship: A ‘carrot’ for President Cyril Ramaphosa to remain

Currently, we don’t know if Mr. Ramaphosa’s cabinet will lean on him to remain for a time if the support is very near 50%. There’s a ‘carrot’ next year, which is the G20, something he may aspire to, although he has previously looked to exit. Rivals exist that would seek to push him out of the party. Our call on balance is that if the support is near 50%, he will likely remain in command for a time. However, he is likely to exit ahead of the next election.

Implications of South Africa’s foreign policy alignment for the West

Observers from abroad should understand that when South Africa transitioned to democracy and the African National Congress (ANC) came to power, it was in a unipolar world. However, that has changed. We now live in a multipolar world, and the ANC has options beyond the West.

Intrinsically, nothing has changed in the party’s positioning. It’s always been somewhat misunderstood in the West. What has changed is the environment around it, which has emboldened the ANC in some of the positions it has taken. A good example of this is the chant ‘from the river to the sea,’ which Mr. Ramaphosa repeated at a massive rally of his party in Johannesburg this past weekend.

South Africa commands the Indian Ocean Rim

Consider the Indian Ocean Rim, which South Africa commands with its significant coastline and remains influential all the way up Africa’s east coast. The Carnegie Endowment sees that Indian Ocean Rim as absolutely critical to future military engagements, specifically the ability to exercise military presence around the major shipping choke points.

If something goes wrong in Suez, a contemporary problem, a lot of global bulk shipping needs to move around the southern tip of Africa, passing South Africa’s east and west coast and the strategically important naval base at Simonstown. This base is almost right on the tip where the Atlantic and Indian Oceans converge off the coast of South Africa.

The Hudson Institute has produced some recent material on how the shipping choke points in the Indian Ocean are becoming increasingly hostile to Western actors and influence. China has made spectacularly successful efforts to expand eastwards into the Pacific through the Solomon Islands and westwards onto Africa’s coastline. There have even been attempts to march through the Mediterranean and Haifa and Italy, what the Hoover Institution ominously called ‘stepping stones to one day rule the Atlantic’.

So, if South Africa, over the next decade, when this question of its foreign policy leanings will be settled, turns firmly westwards or firmly anti-west, the implications from the Indian Ocean are immense.

Strategic importance of the South Atlantic, the West Coast of Africa

The South African naval base at Simonstown commands the entrance from the South into the South Atlantic. There are significant port facilities in Namibia, including a deepwater port at Walvis Bay, South Africa’s immediate northern neighbor. Recently, a massive oil find was made off the Namibian coast. Additionally, the Angolan Ports at Namibe, Lobito, and Luanda can extend all the way up to Bata in Equatorial Guinea, a possibility that some Western national security thinkers are already discussing.

Consider the scenario where China establishes a naval facility that sails from Bata, closer to New York than if it had a naval facility in Hawaii. The opening battles of the first and second world wars were in the South Atlantic. Margaret Thatcher sent the largest battle group since the end of the Second World War to the Falklands, not just because of national pride, but because of the strategic importance.

The direction South Africa is ultimately heading, which this election is starting to answer, has immense strategic implications off both the West Coast and the East Coast of South Africa.

Range of African countries have worse terror indices than Middle East

The security question extends from the oceans to the African mainland itself. Economically, Africa’s population is projected to grow by a billion people over the next 30 years. The continent already has more cities with over a million people than Europe and America combined.

These cities are home to individuals whose ideas will largely determine the voting patterns of their governments on global forums, such as at the General Assembly of the UN. There are 50 such votes. Some Western rivals have written strategic documents about the importance of capturing that market. So, diplomatically, it becomes important.

Economically, cliches such as control over critical minerals become significant, especially if Scotland becomes more hostile to Western actors. The long-term disadvantage they face is quite immense. Then there’s the straightforward consumer market. Africa has changed a lot over the past 50 years. The number of changes of government through coups and assassinations, which is your benchmark, is way down. The share of trade dollars now surpasses the share of aid dollars flowing into the continent.

The consumer market in and around South Africa and southern African states is now two-thirds the size of that of South America and is growing twice as fast. So, if you’re a South African, this election is important, depending on which way it goes.

But if you’re outside and you’re looking at what is going to happen in the election and what that says about the longer-term political drift, then the great unknown, the question of how a future coalition, which is necessarily what we’re moving towards, is put together, and where it leans on foreign policy, the implications are truly spectacular.

Western diplomats’ edge in South Africa is diminishing

We’ve tested some of this, as we’re very interested in the question of foreign policy alignment. On balance, if you ask South Africans whether they lean West or not, you’ll still get answers that lean towards the West, but not definitively so. In fact, it depends heavily on how you phrase the question.

If you phrase the question in a way that suggests there could be disproportionate advantages to turning away from the West and doubling down on relations with Iran, Russia, and China, then you can see the potential to drive public opinion to a point where that is what the process of democratic change in South Africa may ultimately deliver.

Behind the political battle in the country, there’s a battle of the diplomats and positioning. The West probably still has an edge, but it’s a diminishing one. Strategically, Western diplomats now face disadvantages. They tend to deal with state actors, whereas in much of southern Africa, and indeed across the continent, non-state actors are often more influential and important. The West’s global rivals find it much easier to deal with non-state actors.

Demands from the West on climate change is counterproductive to Africa’s development needs

A second problem is that for Africa to succeed, and South Africa particularly so, given the weak economic performance of the past decade, it needs very efficient energy sources and a merit-based economy. However, the effect of cultural wars in the West means that the answers African governments get back to those questions from Western diplomats are now often counterproductive to Africa’s development needs.

The aversion to hydrocarbon threats that South Africa’s government faces to its exports, if it doubles down on its coal fleet to sustain and secure the levels of electricity production necessary to ensure an economic growth recovery, it frankly gets a lot better advice from Russia and China when it asks what to do on energy.

So, the picture from 30 years ago is useful to go back to. In the unipolar world, the advice South Africa would have got from the Western world would have been chiefly sensible and if followed, which it largely was, would secure an economic recovery, which it largely did.

In this new multipolar world, not only does a future South African government have alternatives to lean towards, but the advice it gets from Western capitals is not always in line with the best interests of its economy or the material circumstances of its people. It’s on that point, as much as anything, that Western influence in Southern Africa and around South Africa, if it is to falter to any significant extent, will falter over the next 10 or 20 years.