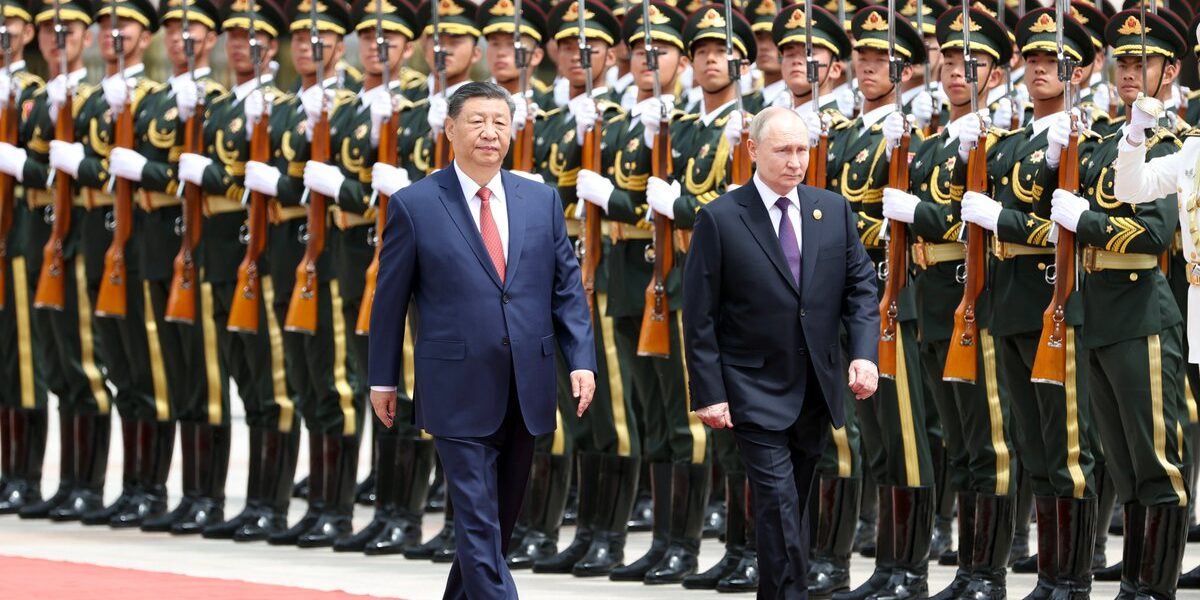

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping held a pivotal meeting in Beijing last week. Xi welcomed Putin with a grand reception, marking the start of what was celebrated as a ‘new era’ of cooperation in an increasingly ‘multipolar world’. This article, republished with permission from the Atlantic Council, features expert analysts examining the potential global implications of this newfound cooperation for the global community.

New Atlanticist: May 16, 2024

Experts react: What will Putin and Xi’s ‘new era’ of cooperation mean for the world?

By Atlantic Council experts

Keep your “friends” close. On Thursday, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met in Beijing to celebrate a “new era” of cooperation in an increasingly “multipolar world.” Putin’s visit comes as Russian forces are ravaging Kharkiv, and just after the Russian president reshuffled his military leadership ahead of an expected summer offensive in Ukraine. Putin is relying on his “dear friend” in China to continue supporting his country’s wartime economy, including through oil purchases. At the same time, Xi is looking to lock in a junior partner for China as its economy faces de-risking by Europe and new tariffs from the United States. Below, Atlantic Council experts delve into what to make of the duo’s meeting and what to look for next.

Click to jump to an expert analysis:

John E. Herbst: Putin and Xi are drawn together by hostility to the United States

Matthew Kroenig: Putin and Xi are afraid the US will join an arms race they already started

Kimberly Donovan: China is the axis of sanctions evasion

Andrew A. Michta: The Putin-Xi meeting shows the ‘axis of dictatorships’ is getting stronger

Shelby Magid: Putin and Xi are masquerading as peacemakers

Markus Garlauskas: Putin and Xi are allies. Their statement should be a wakeup call.

Putin and Xi are drawn together by hostility to the United States

The Putin-Xi bromance’s latest episode comes live from Beijing, where Putin arrived with a largish entourage hoping to persuade his elder brother to offer more support for his still-not-successful aggression in Ukraine. His visit proceeds as his forces continue to make incremental, if casualty-heavy, gains—facilitated by the six-month delay in approving new US aid for Ukraine, inspired by the populist right—and pound Kharkiv with an Aleppo-brutal air bombardment. But they still have achieved no battlefield breakthrough.

The two strongmen and their teams have conducted talks on the state of the international system and enhancing cooperation in their “no limits” partnership. The problem for Putin is that the “no limits” in their partnership appears confined mainly to the rhetorical sphere. The two leaders blasted the United States as a “hostile and destructive” hegemon, declining but still dangerous. They issued a joint statement that talks about a deepened strategic partnership and a “new era.” Yet as they talked about growing cooperation, and even as Russian-Chinese trade flows have grown substantially in recent years, Chinese exports to Russia have declined in recent months. This may well reflect the recent warnings from the United States about providing military aid to Moscow and flouting sanctions policy on Russia. It is well understood that Chinese oil and gas purchases from Russia have helped it weather Western sanctions, but perhaps the Chinese hosts did not want to unduly antagonize the West and, therefore, the head of Gazprom was not part of the Russian delegation to China.

It is noteworthy, too, that Putin praised China’s peace proposals for Ukraine. This is likely part of his bid to persuade China not to attend the mid-June Swiss conference on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s peace formula. Moscow was unhappy when China attended the last conference in Saudi Arabia.

Bottom line: This summit is more of the same. Overall, the two countries are drawn together by hostility to the United States. In a difficult war, Putin is looking for greater Chinese help, both economic and military. China would like Russia to win, but is still wary of provoking the United States and the West with greater support.

—John E. Herbst is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and a former US ambassador to Ukraine.

Xi is decoupling from the US and deepening ties to Russia. It’s a bad deal for China.

We got a good look at the changing global order this week, and it’s not a pretty sight. Two days after US President Joe Biden announced steep new tariffs on a range of Chinese products, Xi welcomed Putin in Beijing, where the two leaders pledged to deepen their countries’ cooperation. A half century ago, China forged ties with the United States after decoupling from the Soviet Union. Now, as China decouples from the United States, it is reconnecting with Russia. Xi thinks this is a good trade for China. He’s exchanging a United States he can’t control with an isolated, declining Russia that he can. And he gets a partner who shares his authoritarian values and mission to create an alternative, illiberal bloc to roll back the dominance of the West.

The problem is that Xi is exchanging ties to a twenty-five trillion dollar economy with the advanced technology China needs for a two trillion dollar economy that’s not much more than a gas station. It’s not a great bargain. That Xi is willing to make it shows how thoroughly he has replaced the pragmatic pursuit of economic development with an anti-Americanism that will potentially jeopardize that development.

—Michael Schuman is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and a contributing writer for the Atlantic magazine.

Putin and Xi are afraid the US will join an arms race they already started

At the geopolitical level, the China-Russia “new era” partnership shows that the world is tightening into geopolitical blocs with growing ties among the revisionist autocrats against the United States and the rules-based order. The autocrats supported each other’s most important revanchist priorities. Putin backed Xi’s position on Taiwan. Xi made oblique statements in support of Russia’s war in Ukraine, endorsing Russia’s efforts to “ensure security” and opposing “outside interference in Russia’s internal affairs.”

They joined together in criticizing the United States for undermining the strategic balance, but we would need Freud to disentangle this level of projection. They accused the United States of deploying “global missile defense” even though China and Russia are building air and missile defenses against the United States, and even though Washington has no such defenses for China and Russia. They accused the United States of building weapons for “potential decapitation strikes,” but China’s fractional orbital bombardment weapon is the best weapon ever invented for this purpose—and is, again, a capability that Washington lacks. Finally, they criticized Washington for planning to deploy short- and intermediate-range missiles in Europe and the Indo-Pacific. Currently, Russia and China have thousands of these missiles, while the United States has deployed zero. Moscow and Beijing seem worried that Washington will decide to run the arms race that these dictators are thrusting upon it.

—Matthew Kroenig is vice president and senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security

China is the axis of sanctions evasion

Putin and Xi’s latest meeting further confirms our assessments that China has become the economic lifeline for Russia in the wake of Western sanctions. Over the past two years, China has become Russia’s primary trading partner and continues to import Russian commodities, especially oil. The two countries are trading in Chinese yuan and Russian rubles, which allows them to circumvent Western sanctions because the transactions are taking place outside of the US dollar, euro, and other Group of Seven (G7) sanctions coalition currencies. We assess that China is moving this activity to its smaller regional banks to protect its largest financial institutions with Western ties from direct sanctions exposure and the threat of US secondary sanctions. However, these transactions are still taking place and providing the revenue Russia needs to continue its war in Ukraine.

It is becoming clearer that China is the axis of sanctions evasion. China continues to prop up Russia, Iran, and North Korea, among other adversarial regimes to challenge US leadership and the global order. Countering Russian aggression in Ukraine is no longer a strictly Russian problem. Policymakers must consider China, Russia, and even Iran and North Korea together—and specifically their financial linkages—when developing sanctions and other measures to address the range of nefarious and destructive activity these regimes are executing.

—Kimberly Donovan is the director of the Economic Statecraft Initiative within the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and a former senior official with the US Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

The Putin-Xi meeting shows the ‘axis of dictatorships’ is getting stronger

The Putin-Xi meeting is another indication that the Russia-China alliance, the core of the new “axis of dictatorships,” which also includes Iran and North Korea, is getting stronger. China has been instrumental in throwing Russia an economic lifeline in the aftermath of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Xi’s recent visit to Europeunderscored the two countries’ shared objective to fracture the Atlantic alliance and bring about a fundamental power realignment across the globe.

Xi will likely be briefed by Putin on Russia’s prospects for success of his spring/summer offensive in Ukraine. Russia’s need for continued supplies and further support from China will likely be high on the agenda as well. An important deliverable from the Sino-Russian summit will be the public message that the two states are closely aligned and are cooperating on a host of defense and economic issues in opposition to the United States and its allies.

—Andrew A. Michta is director of the Scowcroft Strategy Initiative and senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Putin and Xi are masquerading as peacemakers

As Russia continues a relentless campaign of aerial attacks pummeling Kharkiv, and its forces push into northeastern Ukraine, Putin and Xi used the Beijing summit to masquerade as peacemakers and discuss their alleged focus on resolving what they call, incorrectly, the “Ukrainian crisis.”

While Russia’s war in Ukraine persists largely due to China’s enabling, Beijing claims to have a neutral position in the conflict and seeks to paint itself as a good faith actor and potential mediator. Speaking alongside Putin, Xi saidChina will continue to play a constructive role toward the return of peace and stability in Europe.

Last year, China presented its vision for peace—a Kremlin-friendly, twelve-point statement with broad principles for ending the war with a political settlement. It notably neglected to call for Russia’s withdrawal from occupied parts of Ukraine. The plan was widely rejected by Ukraine and the West, save for a few Russia-friendly leaders such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

One day before heading to China, Putin declared his support for China’s peace plan. This declaration also comes a month ahead of an alternate initiative working to pave a way to end the war—the high-level Global Peace Summit to be held by Ukraine and Switzerland. The summit aims to lay the groundwork for a comprehensive and lasting peace in Ukraine, on starkly different terms than the Russian-endorsed Chinese plan.

The Ukrainian-Swiss summit is gaining momentum, with at least fifty countries confirmed to participate and 160 invited. While Russia has not been invited, Chinese participation is a key focus in the goal of getting a broad turnout, especially from the Global South. China has not yet agreed to attend, though in line with its stated focus on resolving the conflict, China’s ambassador to Switzerland previously said that Beijing may take part in the summit.

Following the Xi-Putin summit’s declarations on peace, the question remains whether China will attend and try to play a part in any efforts for peace that aren’t just squarely on Russia’s terms.

—Shelby Magid is the deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center.

Putin and Xi are allies. Their statement should be a wakeup call.

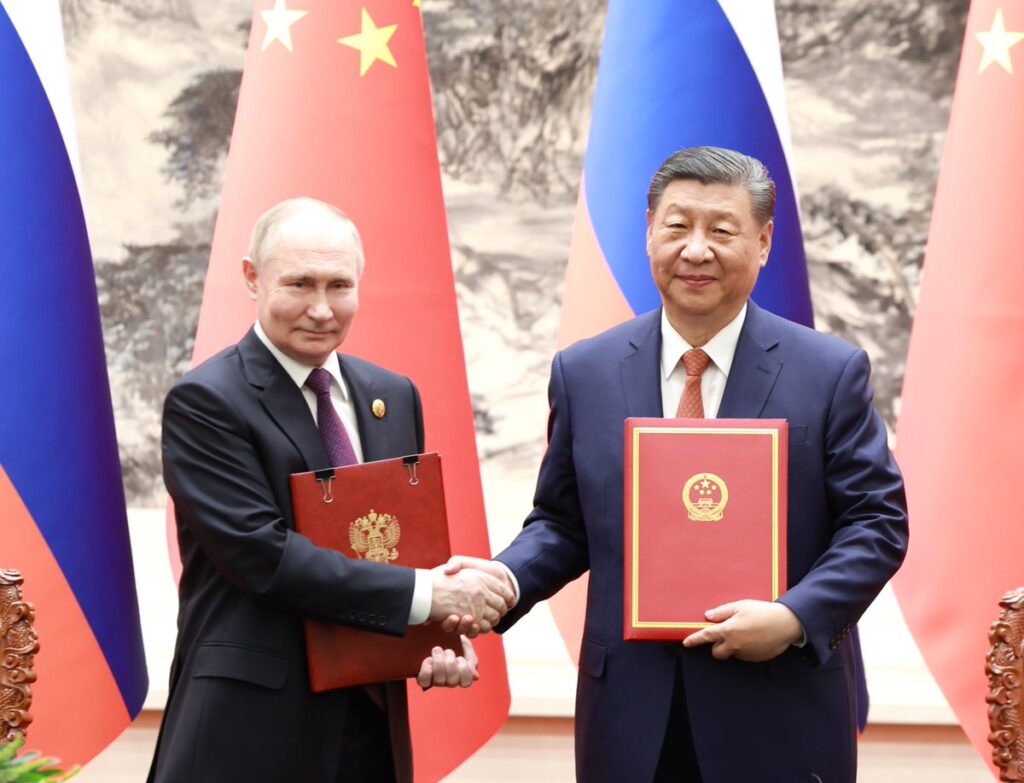

Today’s formal Putin-Xi statement describes a shared worldview and aims, along with specific strategic cooperation measures to support them. It is a comprehensive statement of a de facto alliance, and it does not even cover everything China and Russia are already doing to support each other. Beijing and Moscow are unlikely to sign a document as clear as Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy did with the “Pact of Steel” or the “Tripartite Pact” that added Imperial Japan—at least not anytime soon. They do not need to.

Russia is currently engaged in an active war of aggression against Ukraine that would have long since sputtered out into clear defeat without the tremendous diplomatic, informational, technological, and economic support China has provided. That Russian-, North Korean-, and Iranian-made weapons, rather than Chinese-made ones, are striking Ukraine is missing the forest for the trees. China has provided aid that is vital to Russia’s sustainment of its offensive against Ukraine, and China provided what was needed to enable Russia’s stubborn defense against Ukrainian counterattacks. Further, by enabling sanctions evasion, China has created the international conditions that make it possible for Iran and North Korea to provide such weapons to Russia with near-impunity. In practical terms, China has done far more to sustain Russia’s war effort against Ukraine than Imperial Japan ever did to sustain Nazi Germany’s, or vice versa.

For years, we have been in a new strategic era where Xi’s China and Putin’s Russia are increasingly aligned and cooperating closely, and this has only been accelerated by Putin’s war against Ukraine. Observers should not be reassuring themselves that Putin and Xi are not really allies because they have not signed a formal mutual defense treaty or because Chinese weapons and forces have not joined Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. The actions are there; the formal statements are there. Let us call this relationship what it is: an alliance.

Even if this Xi-Putin alliance is not built on foundations as strong as those of the US alliance system, Washington and its own allies and partners around the world should not fail to see this alliance for what it is—and they should adjust their plans, policies, and strategies accordingly.

—Markus Garlauskas is the director of the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. He is a former senior US government official with two decades of experience as an intelligence officer and strategist.