Nuclear power will be a key part of a suite of new energy infrastructure built to meet surging data-center power demand driven by artificial intelligence. But nuclear can’t meet all of the increased data-center power needs. Natural gas, renewables, and battery technology will also have a role to play, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

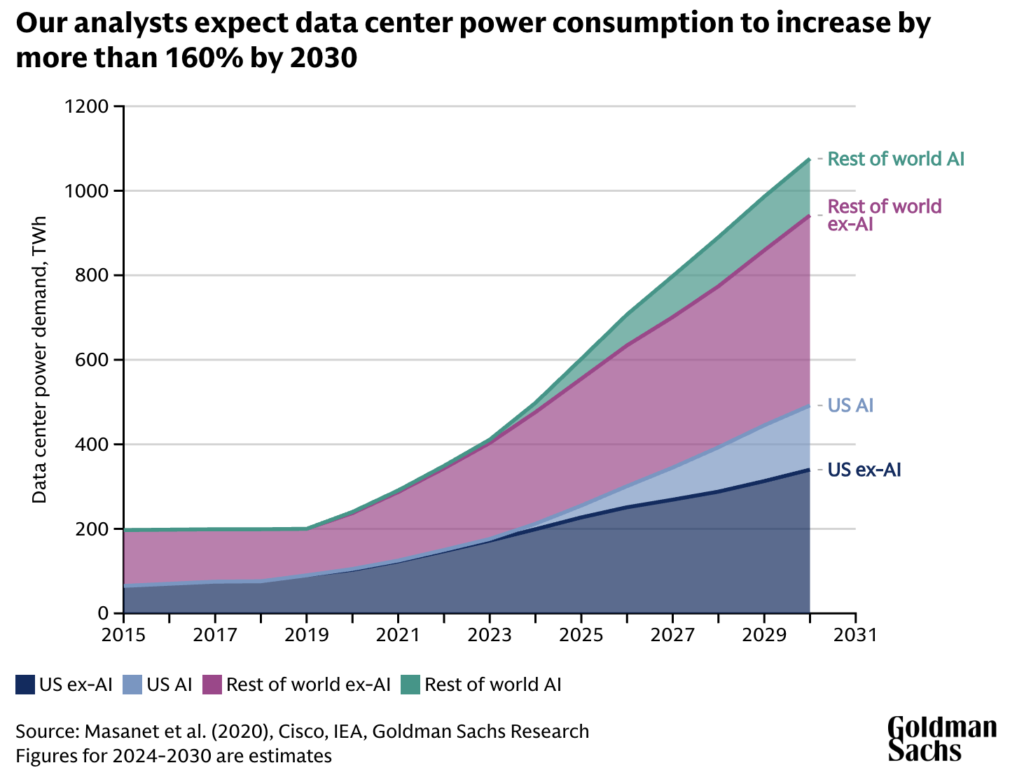

Several big tech companies looking for low carbon, round-the-clock energy signed contracts for new nuclear capacity in the last year, and there could be more such deals ahead. Those efforts come as electricity usage by data centers is expected to more than double by 2030, according to reports led by Brian Singer, Jim Schneider, and Carly Davenport.

In total, the team forecasts 85-90 gigawatts (GW) of new nuclear capacity would be needed to meet all of the data center power demand growth expected by 2030 (relative to 2023). But well less than 10% will be available globally by 2030.

As power needs ramp up, the efficiency gains of data center infrastructure are beginning to slow, according to Davenport, a US utilities research analyst in Goldman Sachs Research. “Growth from AI, broader data demand, and a deceleration of power efficiency gains is leading to a power surge from data centers,” she writes.

How much is AI power consumption expected to rise?

Power demand from data centers is on track to grow more than 160% by 2030, compared to 2023 levels, Goldman Sachs Research projects. A scenario in which 60% of that increased demand was met by thermal sources such as natural gas would lead to an expected emissions increase of 215-220 million tons globally, equivalent to 0.6% of the world’s energy emissions.

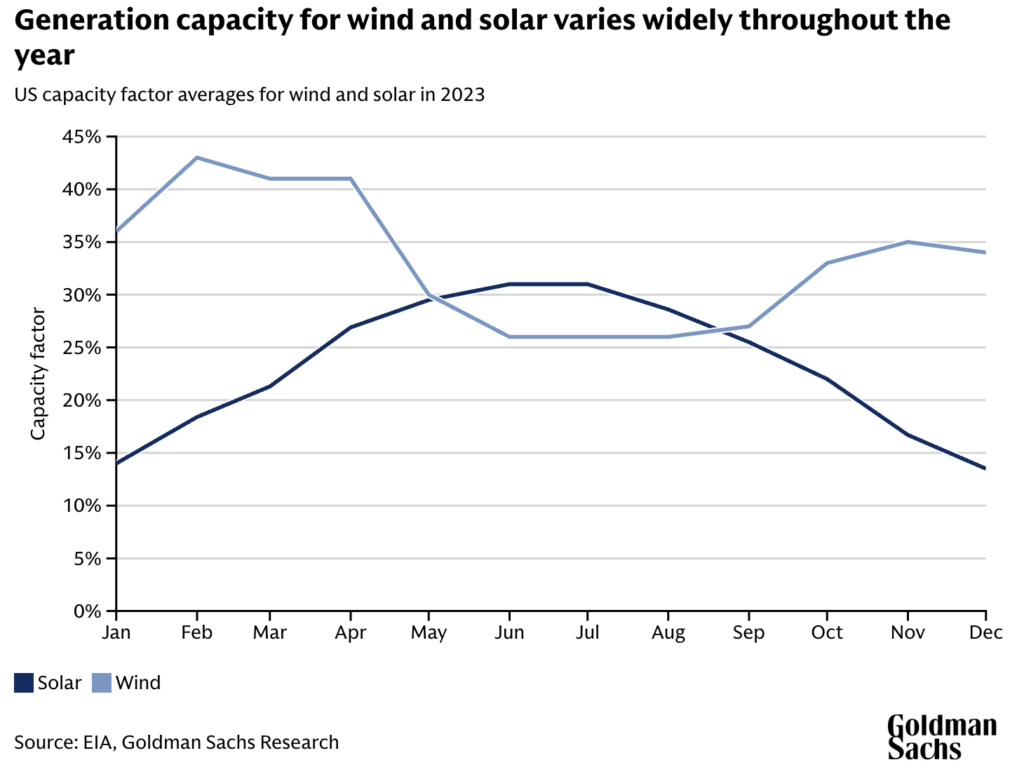

While renewables have the potential to meet most of the increased power needs from data centers at some times of day, they don’t produce power consistently enough to be the only energy source for data centers, explains Schneider, a digital infrastructure analyst in Goldman Sachs Research. “Our conversations with renewable developers indicate that wind and solar could serve roughly 80% of a data center’s power demand if paired with storage, but some sort of baseload generation is needed to meet the 24/7 demand,” Schneider writes. He adds that nuclear is the preferred option for baseload power, but the difficulty of building new nuclear plants means that natural gas and renewables are more realistic short-term solutions.

Nuclear energy has almost zero carbon dioxide emissions — although it does create nuclear waste that needs to be managed carefully. But the scarcity of specialized labor, the challenges of obtaining permits, and the difficulty of sourcing sufficient uranium all pose a challenge to the development of new nuclear power plants.

By the 2030s, though, new nuclear energy facilities and developments in AI could start to bring down the overall carbon footprint of AI data centers.

In the meantime, companies trying to supply energy for new data centers are likely to focus on a mix of power sources, writes Singer, global head of GS SUSTAIN in Goldman Sachs Research. “Our outlook on power demand growth warrants an ‘and’ approach, not an ‘or’ approach, as we see ample opportunities for generation growth across sources,” he writes.

How much will nuclear power increase?

Recent contracts for nuclear energy facilities along with signs of countries’ greater appetite for nuclear power suggest a significant increase of investment in the next five years, and a corresponding rise in power supply in the 2030s.

The proliferation of AI data centers has boosted investor confidence in future growth in electricity demand at the same time as big tech companies are looking for low-carbon reliable energy. This is leading to the de-mothballing of recently retired nuclear generators, as well as consideration for new larger-scale reactors.

In the US alone, big tech companies have signed new contracts for more than 10 GW of possible new nuclear capacity in the last year, and Goldman Sachs Research sees potential for three plants to be brought online by 2030.

Meanwhile, governments are also broadly more supportive of nuclear power. Switzerland is reconsidering the use of nuclear generators for its electricity supply, while nuclear power enjoys bipartisan support in the US, and the Australian opposition party has put forward plans to introduce nuclear reactors. Participants at the COP28 conference in late 2023, an annual summit convened by the UN to address climate change, agreed to triple global nuclear capacity by 2050.

Building the ‘green’ data center

Green energy sources are also receiving considerable investment from AI providers. The team forecasts that 40% of the new capacity built to support increased power demand from data centers will be renewables.

The supply cost of renewable energy sources is cheaper than generating electricity from natural gas, before taking into account transmission considerations and filling gaps when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. Analysis by Goldman Sachs Research shows that, at face value, the average cost of energy for onshore wind hosted on the site of a data center is $25 per megawatt hour in the US, while solar energy costs $26/MWh, and combined cycle natural gas (the most fuel-efficient type of gas-fired power plant) costs $37/MWh before accounting for the cost of carbon capture.

In practice, though, utility-scale solar plants only run around 6 hours per day on average, while wind plants run for an average of 9 hours per day. There is also day-to-day volatility in the capacity of these sources, depending on the radiance of the sun and the strength of the wind.

Transmission costs are also a consideration for data center operators. Because renewable energy sources often take up a much greater land footprint than natural gas or nuclear, they are more likely to be located away from big cities, where much of the energy that they generate is used. As a result, the energy they generate may have to travel further before it is used.

On the other hand, thermal plants — such as those powered by nuclear reactors or combined cycle natural gas — can run throughout the day, without hourly intermittency challenges.

For these reasons, the team expects technology companies to take advantage of a combination of all of the above power sources. In recent months, hyperscalers and cloud computing companies have signed multiple contracts for larger-scale nuclear, small modular reactors (SMR), renewables power purchase agreements, and carbon removal.

Natural gas will stay in the mix

Currently, a round-the-clock power solution that meaningfully reduces emissions comes with a premium. In the US, low-carbon options cost between $19-72 more than the baseline natural gas combined cycle per megawatt hour.

Unlike the EU, the US doesn’t have a federal carbon pricing mechanism. But some American companies are choosing to internally attach a price to carbon emissions.

Adding a price of $100 per ton for carbon dioxide meaningfully offsets the Green Reliability Premium. This would move the cost of natural gas combined cycle to $91/MWh based on historical reported gas-fired power emissions intensity, compared to $87/MWh for a near 100% renewable energy solution including offsite solar or wind power and battery storage, and $77 for a large-scale onsite nuclear generator, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

To provide round-the-clock power, data centers are looking to augment solar and wind power using battery storage and either power provided from the grid or onsite natural gas peaking capacity (a power plant that runs during periods of high demand or to fill gaps in intermittent generation). Our analysts estimate a combined solution of solar, battery storage and natural gas would lower emissions by 67% compared to baseline combined cycle natural gas. The team believes the financial impact to major hyperscalers from paying the “Green Reliability Premium” associated with these technologies is modest.

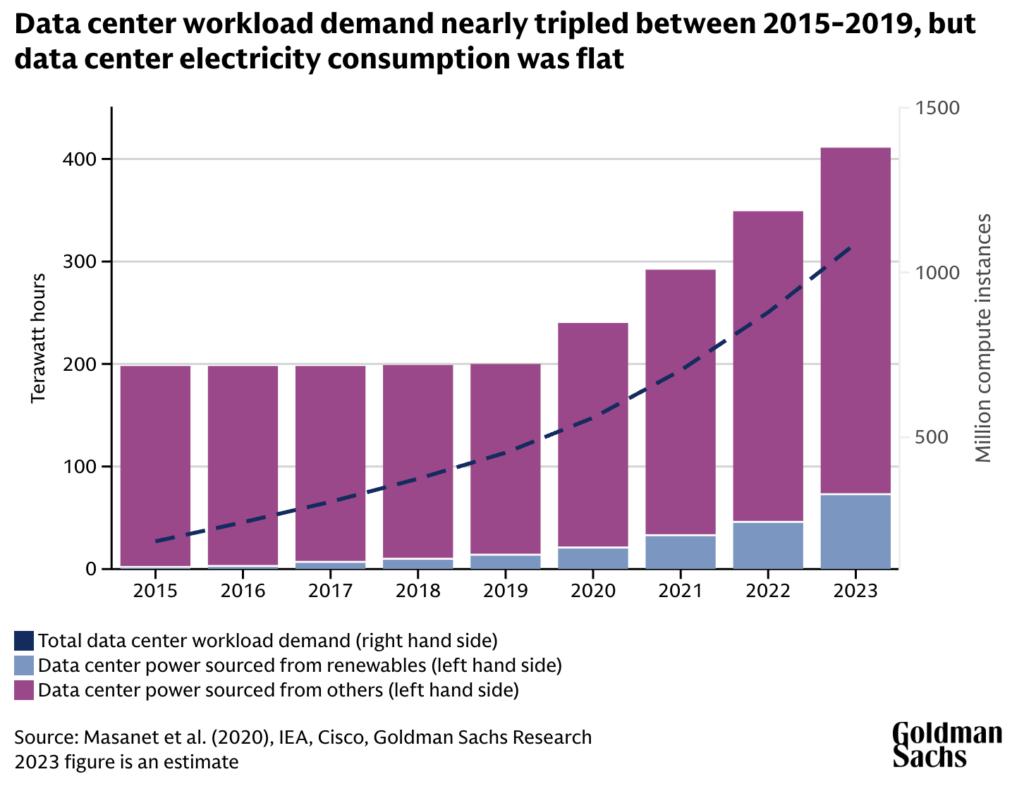

In addition to finding greener energy sources to power data centers, technology providers can reduce the emissions intensity through efficiency gains. This was the case in 2015-2019, when the workload demand for data centers nearly tripled, but their power consumption remained flat due to improvements in energy efficiency.

Since 2020, efficiency gains have decelerated, but the team expects more innovations to help lower the power intensity of data centers in future.

This article was published by Goldman Sachs.